Chapter from the monograph “ICTY and Srebrenica.”

How does ICTY get away with proving mass murder ascending to the level of genocide when the bulk of the evidence does not support many of its factual conclusions? We can try to answer this question by reviewing the evidence which various ICTY chambers used to reach their conclusions. We will review and test the evidence for the Pilica/Branjevo massacre site narrative, then the evidence for the alleged events that took place at Kravica, also the site of a massacre. Both episodes of mass murder occurred within the larger context of the execution of Muslim prisoners of war captured by Serbian forces following the takeover of Srebrenica on July 11, 1995. The evidentiary basis will be tested to assess the degree of correspondence between the evidence presented (or ignored) in open court and the conclusions that the chamber ultimately reached.

I

Our first case study will test the way in which evidence, broadly understood, was treated by The Hague Tribunal by focusing on the massacre at Pilica/Branjevo.

The prisoners were initially quartered at a facility in Pilica. They were then taken to a nearby field in Branjevo, where they were shot. This massacre was one of a series of similar episodes which occurred over a week’s time in the final stages of the Bosnian war and after the fall of Srebrenica on 11 July 1995. The ICTY maintains that these episodes collectively constituted the Srebrenica massacre.[1]

The focus on Pilica/Branjevo (generally referred to as “Pilica” because that was where prisoners were assembled prior to execution, while nearby Branjevo is the location of the field where the killings took place) is deliberate because of its paradigmatic character. The principal witness, Dražen Erdemović, ultimately signed a plea-bargaining agreement with the ICTY Prosecution. This agreement obligated him to testify at all Srebrenica-related trials, where retold his story with greater or lesser consistency and persuasiveness. There are also two alleged survivors of the massacre who have also given evidence.

II

What happened in Pilica? Here follows a brief and relatively uncontroversial recital of the basic facts.

On 11 July 1995, Serbian forces completed a successful offensive and shut down the then-protected enclave of Srebrenica. Under an agreement signed in April 1993, the enclave was supposed to be demilitarized in exchange for the Serbs’ halting their military operation, which had threatened to defeat the forces within Srebrenica that were loyal to the Sarajevo authorities. Prior to April 1993, forces from Srebrenica conducted a widespread and systematic campaign against Serbian villages and settlements in the area. The 2002 Dutch Government NIOD Report said that an estimated “1,000 and 1,200 Serbs died in these attacks, while about 3,000 of them were wounded…. Ultimately, of the original 9,390 Serbian inhabitants of the Srebrenica district, only 860 remained…”[2] After the April 1993 truce which declared Srebrenica to be “a safe area,” Srebrenica forces loyal to Sarajevo openly ignored the demilitarisation provision; the fully armed 28th Division of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina remained in control of the enclave; attacks, ambushes, and provocations from the Srebrenica “safe area” against surrounding Serbian settlements continued unabated.[3]

Serbian forces, motivated to avenge their civilian losses, occupied the Srebrenica enclave in July 1995, whence they safely evacuated[4] about 20,000 inhabitants, mostly women, children, and the elderly, to Muslim-held territory about 50 kilometers away. Serbian forces engaged in armed clashes on numerous occasions with a mixed Muslim military/civilian column, which was estimated to number between 12,000 and 15,000 men, and which was conducting an armed breakthrough from Srebrenica and heading toward Muslim lines near Tuzla. During the numerous clashes, many members of the column were killed in combat; others were captured. Of those captured, some were transferred to a prisoner-of-war camp and ultimately exchanged; others were summarily executed by a possibly rogue outfit called 10th Sabotage Detachment, to which Prosecution witness Dražen Erdemović had once belonged.

Erdemović’s account of events states that on 16 July 1995 some of the Muslim prisoners, alleged by Erdemović to have numbered about 1,200, were transported from a detention center in Pilica to a field on a farm in nearby Branjevo. Between approximately 11:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m., a firing squad of eight men, one of whom was Erdemović, executed these prisoners. Another 500 prisoners who were being held at a different location in Pilica were executed later that afternoon by another firing squad.

In March 1996, Erdemović contacted the media as well as the ICTY. He claimed that he was suffering pangs of conscience for his actions, yet he also expressed the hope that in exchange for his cooperation as a witness for the ICTY Prosecution he would be granted immunity from prosecution and would be accorded resettlement — along with his family and under a new identity — in a Western country.[5]

The other allegedly percipient witnesses to the Pilica massacre were Protected Witness Q and Ahmo Hasić, who has testified with and without protective measures. Both claim to have luckily escaped from the execution site on 16 July 1995.

It is time now to turn our attention to both the witness and the forensic evidence to determine what it indicates about the events that took place in Branjevo.

III

The Dražen Erdemović narrative.[6] The Prosecution of the Hague Tribunal has frankly acknowledged that before Erdemović’s transfer to the ICTY by Yugoslav authorities on 30 March 1996 (that is to say, nine months after the fall of Srebrenica) it knew nothing important about the Pilica massacre,[7] which eventually became the best documented episode in a series of mass prisoner executions that compose the alleged Srebrenica genocide. At Erdemović’s trial in The Hague on 19 November 1996 (a year and four months after the events in Srebrenica charged in the indictment), Jean-René Ruez, the ICTY Chief Investigator in charge of Srebrenica, said that even at this late stage Erdemović was still the Prosecution’s only source for information about the major killing operation that allegedly took place in Pilica.[8] So, presumably he must have had important and probative evidence to give. His evidence, therefore, should have been crucial to sorting out one major episode in an interconnected series of crimes which are said to amount to – genocide.

Erdemović’s alleged personal involvement may have been a good starting point, but the obligation of proper conduct on the Prosecution’s part included a good faith effort to verify allegations intended to be used as evidence, and likewise excluded the use of any uncorroborated assertion just because it happened to support the Prosecution’s case. In the adversarial system of justice,[9] the Prosecutor’s obligation as an “officer of the court” is to check the facts before presenting them to the Chamber to ensure that the version of events is internally consistent and credible — or at least appears that way. To what degree have these requirements been met in the case of Dražen Erdemović, the star witness who is cooperating with the Prosecution?

To start with, the manner in which he burst on the scene in the Srebrenica controversy should have set off alarm bells for any dispassionate observer. On 3 March 1996, while recuperating in Serbia from wounds he sustained in a shootout with another member of his unit — possibly over the division of spoils from the alleged massacre[10] — Erdemović invited French journalist Arnaud Girard and his American colleague Vanessa Vasić-Jeneković to hear his dramatic revelations. The interview resulted in a long article that appeared in Le Figaro on 8 March 1996. The key portion of the interview, which bears on Erdemović’s motives and which should have aroused critical examination by the present journalists as well as by the ICTY Prosecutor and Chamber, is this:

The former soldier who has reported these facts has been negotiating with the Tribunal in The Hague. In return for the promise of immunity and the possibility of resettling in the West with his family, he is ready to tell all.[11]

So, it should have been clear right at the outset to all the interested parties that Erdemović’s motives were, if not completely corrupt, then at least mixed. In addition to salving his conscience (if we are to give him the benefit of the doubt), he clearly presented as his motive the desire to start a new life elsewhere, far from the reach of his querulous co-perpetrators and, even more importantly, with immunity from prosecution for the horrendous crimes he was describing and in which he was also admitting participation. Quid pro quo was obviously on his mind, and he signalled it from the start. So, the first logical question that any careful investigator and trier of fact would ask is: to what extent might these motives have colored, influenced, or enhanced his narrative to fit the expectations of the Prosecution, from whom he was expecting not only refuge but also immunity?

The general picture of the executions at Branjevo has been largely consistent to the extent that witness Erdemović has repeatedly testified in several trials that the process began around 10:00 a.m. or 11:00 a.m. on 16 July and was over by about 3 p.m. the same day, and that the prisoners were shot in groups of ten.[12] The central claim which makes his evidence vitally important to the Prosecution is his estimate that in that time period — about five hours — Dražen Erdemović and seven other members of an execution squad drawn from the Tenth Sabotage Detachment shot, by his estimate, between 1,000 and 1,200 Muslim men who had been captured by Serbian forces after the fall of Srebrenica a few days earlier.[13] It is clear that demonstrating that as many as 1,200 Srebrenica victims were shot at a single location over the course of five hours would put the Prosecution well on its way to proving the cold blooded murder of 8,000 prisoners of war; however, if the ICTY chambers who accepted Erdemović’s testimony had critically examined the mathematical feasibility of his claim from a time-study engineering standpoint, some serious questions would immediately have been raised. And perhaps some hasty conclusions might have been avoided.

Five hours is 300 minutes, and 1,200 prisoners come to 120 groups of ten. Dividing 300 minutes (the period of time the executions lasted according to this witness) by 120 (the number of groups), we get about 2.5 minutes per group of ten men (as he claimed) to walk the 100-200 meters from the bus to the execution site, throw their IDs and valuables into a pile, to be shot — and finally for a Serbian soldier to check for survivors and finish them off before the next group of ten was brought to go through the same routine. How likely is this scenario in the time frame indicated by Erdemović? For comparison, a similar massacre said to have taken place in nearby Orahovac[14] involved the execution of 1,000 prisoners, somewhat less than the top figure alleged by Erdemović. Oddly, the Chamber there concluded that the Orahovac executions started on 14 July 1995 in the afternoon and continued all evening and into the morning of the following day, 15 July, and finally ended at 5:00 a.m. While the same Blagojević and Jokić Chamber validated Erdemović’s chronologically tight Branjevo narrative,[15] it apparently failed to notice the incongruity of this story with its other findings in the same judgment about analogous events that took place in Orahovac. However, the Chamber sensibly, at least, gave the Orahovac executioners three times as much time to perform a task of similar magnitude and complexity as the one in Branjevo. In Branjevo, the firing squad must have been really quick on the draw.

But mathematical computation (for the length of time required to perform these acts) is not the only questionable aspect of witness Erdemović’s report about what happened in Branjevo. Apparently, Erdemović had taken care to portray his role in the killings in a light that he thought would most likely minimize his own criminal responsibility. He testified on various occasions that he held the rank of sergeant in the Tenth Sabotage Detachment, the unit from which the executioners were drawn, and he testified that in 1994 he joined the outfit with the rank of sergeant. But he claimed that in April 1995, just months before the July massacre in which he admitted to having taken part, he was demoted by his superiors to the rank of private for an infraction he had committed. One marvels at the convenient timing. The demotion is of some importance in his narrative[16] because he constructed an image of himself as an unwilling executioner, verging on a conscientious objector, who grudgingly went along and — by his own admission — executed 70 to 100 prisoners in Branjevo because, being a mere private, he was himself threatened with execution if he had refused. Ever since the Nuremberg Trials, “following orders” has not been a valid excuse for participating in atrocities; however, Erdemović is not a lawyer but an unemployed locksmith, so, being a layman, he may have been uninformed on this point. He just tried to do what he thought was best to minimize his own liability, though an alert Prosecution and Chamber would have questioned how this comports with his insistent proclamations of repentance.

The Prosecution and Chamber had plenty of evidence to make them question the veracity of Erdemović’s testimony. For one thing, the 10 July 1995 Order issued by the detachment commander Milorad Pelemiš for the unit to join battle in Srebrenica unambiguously lists Erdemović as a “sergeant”[17] at a time he claimed he was a simple soldier. Moreover, his immediate superior in the chain of command, Col. Petar Salapura, flatly contradicted Erdemović’s claim of demotion in his own testimony.[18] This claim was also debunked by Dragan Todorović, the unit’s logistics officer, who was very well acquainted with Erdemović as well as his status.[19] These credible denials of Erdemović’s claim that he was a lowly private at the time he participated in the massacre assume additional weight in light of his further claim — which strains credulity — that another simple soldier, Brano Gojković, was actually in charge of the execution squad in Branjevo even though one of the Tenth Sabotage officers, Lt. Franc Kos, was also present among the executioners and was presumably taking orders from Private Gojković.[20]

Erdemović also reported that when the killing was over in the afternoon, the same lieutenant-colonel who had brought them there that morning and who had then left, now reappeared and announced to Private Gojković, whom as we already noted was supposed to be in charge, that there were an additional 500 prisoners in another facility in Pilica who also needed to be executed. Gojković then conveyed this order to Erdemović. Erdemović replied that he had by then tired of executions and refused the order despite the fact that he was a mere foot soldier. He no longer claimed that he was threatened with death for insubordination. The high-ranking officer and Gojković then ordered another group of soldiers to carry out the further execution of prisoners. They ignored the presence of Lt. Kos, who presumably would have been more suitable as the lieutenant-colonel’s interlocutor, if one takes the normal chain of military command into consideration.

The confusion about who was in charge at the execution site is compounded by the ICTY Prosecution’s manifest desire to link the Serbian supreme military commander, General Ratko Mladić, as directly as possible to the commission of a crime. From the prosecutorial point of view, this is perfectly understandable and it is a legitimate way to proceed. One would think, however, that the concept of Command Responsibility, long settled by the Tribunal, would serve as the legal mechanism to achieve this. But apparently, in the Prosecution’s view, it was insufficient. So, at the Milošević trial the Prosecution produced a document purporting to be the Enlistment Contract Dražen Erdemović had signed when he joined the Tenth Sabotage Detachment.[21] The main feature of this otherwise unremarkable document is what appears to be the signature of “Colonel-General Ratko Mladić” in the lower right hand corner on p. 2 of the Contract. Underneath Mladić’s purported handwriting is the signature of Platoon Commander Milorad Pelemiš, who would presumably be expected to sign off on such a document. [See Annex I.]

The controversy, if there is one at all, obviously centers on Mladić’s signature. The Prosecution has a strong interest in validating this document judicially, even though it has been circulated exclusively in the form of photocopies, of which the original has never been produced — it has never even been requested in court. Nor has its provenance, in other words, the chain of custody of this document, ever been presented in court. The latter point (without minimizing the former) is important because of the specific history surrounding this document. Erdemović presumably brought it with him to Serbia in early 1996 when he arrived from Bosnia to receive medical treatment after having been injured in the aforementioned shootout with his firing squad companions in Bijeljina. On the evening of 3 March, Yugoslav State Security arrested Erdemović after he had given his interview to the French journalist Arnaud Girard, and it also seized his personal documents as well as his belongings. Yugoslav State Security kept his personal effects after extraditing him to the ICTY on 30 March 1996. His personal items were not sent to the Tribunal until 12 November 1996, shortly before Erdemović’s trial was scheduled to begin. No itemized list of personal belongings, presumably forwarded by the Yugoslav authorities to the Tribunal, has ever been presented in court; one is simply compelled to assume, without any particular evidence, that this is how the Enlistment Contract came into the Prosecution’s possession. It popped up at the Milošević trial and, predictably, it appeared again at the trial of General Ratko Mladić.[22] The chain of custody of the Shroud of Turin is clearer than the chain of custody of this key piece of Prosecution evidence that links — with compelling directness — Supreme Commander Mladić to a lowly sergeant assigned to an obscure detachment. This conveniently results in a nexus where the evil deeds to which Erdemović confessed can be neatly imputed to Gen. Mladić as well, without the tedious business of going through the chain of command, even as a mere formality.

To return to the first point, the widespread — more correctly, exclusive — use of photocopies as evidence at the Tribunal must be highlighted. Defense teams routinely fail to request original copies, as they would in ordinary criminal cases before domestic U.S. courts, in order to demand vigorously, if necessary, that the best possible evidence be made available for proper forensic analysis. At the ICTY, there is a tacit understanding by and among the Prosecution, the Defense, and the Chamber that requesting originals, whether they be documents or radio intercepts, is simply not done. This unspoken convention has a chilling effect on any attempt to authenticate key evidence. This point requires no further elaboration.

This aspect of The Hague Tribunal’s practice lends itself well to reductio ad absurdum. Instead of contesting the validity of Erdemović’s enlistment documents, which bear Gen. Mladić’s signature, since absent the original this is a futile undertaking, we decided to resort to Photoshop in exactly the same way that we suspect the Prosecution has done. It was no technical challenge at all to substitute the signature of General Charles de Gaulle for that of General Ratko Mladić in the document. [See Annex I.] If photocopies are the best available evidence in this case, then both versions of Erdemović’s Contract must be deemed equally authentic. How General de Gaulle, who passed away in 1970, could have signed an Enlistment Contract dated 1 February 1995 is a puzzle we leave to the Chambers of The Hague Tribunal to sort out.

The confused chain of command is just one of the problems found in Erdemović’s evidence. The figure of 500 additional prisoners allegedly slain in Pilica later that same afternoon is also of material importance. Added to the alleged total in Branjevo, that makes about 1,700 Srebrenica victims, which constitutes about 20%, of the aggregate total of 8,000. So, it is important to establish the authenticity of the figure of 500 prisoners allegedly killed during the final act of the execution drama in the Cultural Centre in Pilica during the final act of the execution drama, as described by Erdemović.

It turns out to be a case of double hearsay. Erdemović reported what Brano Gojković said to him about the number of those prisoners, while Brano Gojković heard it from the unidentified high-ranking officer.[23] After refusing to carry out these additional executions, Erdemović and several of his now weary firing squad companions went to a café across the street from the Cultural Centre, where the on-going shooting was still clearly audible. Once again, there is no percipient evidence about the act itself or the number of victims.

Despite the multiple hearsay in the evidence of “crown witness” Dražen Erdemović, the Prosecution at the Karadžić trial decided to enhance the impact of Erdemović’s assertions, but it was done in a manner so comical that it lowered the Court’s problematic reputation even further down to the level of opéra bouffe.

In the Popović case, the Prosecution introduced witness Jevto Bogdanović[24] to confirm the basic outline of Erdemović’s story about the alleged execution of 500 prisoners in Pilica — but what was the actual testimony this witness gave? Footnote 18643 in the Karadžić judgment approvingly directs us to p. 11333 of the transcript in the Popović case. This is Bogdanović’s testimony as it appears in the Karadžić judgment:

Q. When you were drinking that day, could you say what it was you were drinking?

A. Rakija brandy.

Q. Where did you get that?

A. Neighbours, the locals, brought that to us. We drank for courage, to be able to sustain looking at the blood and the bodies, and the brains of the people.

Q. During the course of that day, did you hear anybody mention a number of how many bodies were in the dom[25]?

A. I heard somebody on the road saying that there were 550, but we ourselves did not count.

Q. But based on your work that day, does that number seem a reasonable number to you?

A. Well, it does. It should.[26]

How did the ICTY transform mere hearsay into a reputable finding of fact? It’s very simple: The Hague Tribunal considers multiple hearsay to be a legitimate evidentiary tool. Hence, the ICTY is receptive to the testimony of a witness who admits to having been drunk while taking part in the post-execution removal of bodies at the Pilica Cultural Center (see Popović et al., Transcript, 10. May 2007, p. 11329). Then this witness passes on to the Chamber remarks made to him in passing by an unidentified individual, while the witness’ judgment, and perhaps recollection of events could have been impaired by excessive consumption of alcohol during the period of time in question. In several ICTY judgments, the number of prisoners alleged at one time by Erdemović, and then by Bogdanović at another, to have been executed in Pilica, which is about five hundred, was declared established and is now, presumably, written in stone: it is history. No reliable witness has ever testified under oath, in any court, to seeing 500 or 550 prisoners at the Pilica Cultural Center prior to the alleged execution, nor has anyone ever testified under oath about the later collection and accounting for the number of corpses. This narrative, which verges on pulp fiction, is unsupported by a shred of objective evidence, yet it has been solemnly enshrined in four separate judgments[27] as a judicially established fact by The Hague Tribunal.

Is there another court anywhere in the entire world where such a thing would be possible?

IV

So much for the alleged witness-perpetrator Dražen Erdemović and his evidence. There are also two alleged survivors who have equally interesting narratives: Protected Witness Q[28] and Ahmo Hasić, who testified variously under pseudonyms as well as in propria persona. In order not to violate ICTY rules, we will focus here only on the evidence that Mr. Hasić gave under his real name.

Witness Q. This witness’ evidence encompasses several different segments of the events that took place at Srebrenica. We will discuss only the portion relevant to Pilica/Branjevo. In essence, Q has claimed that on 14 July he was bused with a number of other prisoners from the town of Bratunac, near Srebrenica, to the schoolhouse in Pilica, about 60 km to the north. There he spent two nights under unpleasant conditions. On 16 July, busloads of prisoners were driven from Pilica to a field on a farm in Branjevo, about a ten-minute ride from there, to be executed. Now this is where the first significant anomalies in his evidence occur. In different trials, Q testified variously that he and his group arrived at the execution site at: 7:45 that morning:[29] between 9:00 and 9:30 a.m. that morning;[30] and “after 4:00 p.m.”[31] that day, with the executions in this version lasting into the night. The third time frame seriously conflicts with Erdemović’s account, according to which it was all over by 3:00 to 4:00 p.m., depending on the trial Erdemović testified in. The commencement of the executions on the morning of 16 July also diverges considerably from Erdemović’s testimony. The discrepancies do not simply concern the time, but also the condition of the field, which, on the one hand, according to Erdemović’s testimony, was empty when he and his group arrived at the field; while witness Q, on the other hand, claims that there were already a number of corpses there. Even so, the spectacularly problematic aspects of Q’s narrative are yet to come.

The most intriguing question, of course, is how Q managed to survive and tell his story. Briefly, it happened as follows. Q claims that the executioners simply began shooting after he and his group had been lined up in the field without the usual order of ready, aim, fire. Miraculously, Q fell face down to the ground with his hands tied behind his back faster than his executioners’ shots travelled, so he dodged their bullets before they could strike him.[32]

Q’s hands were still tied behind his back as he lay on the ground pretending to be dead. He heard Serbian soldiers approaching the recently executed lot and heard one of them comment to the other, as they were getting nearer to him, that shots to the head were messy and that it was better to stop administering the coup de grâce to the head, and to shoot the victims in the back instead because brain matter tended to splatter all over the executioner’s clothing.[33] But this grotesque flourish to the narrative makes no sense. The laws of kinetics dictate that, in a situation such as Q is describing, brain matter would splatter not from the bullet’s point of entry upwards toward the shooter, but through the exit point and downward to the ground. There was in fact no risk of an executioner soiling his clothing in this fashion. These are the hallmarks of a make-believe horror story.

According to the chronology of his narrative, just minutes later Witness Q luckily cheated a bullet intended for him a second time. The fastidious administrators of the coup de grâce did not want to soil their uniforms, so, as they were standing above witness Q, they agreed to avoid shooting the victims in the head. But they were bad shots, so they missed Q’s back and the bullet instead passed just beneath his armpit, between his arm and torso, without grazing him.

This is truly amazing when one considers that Q testified that his arms had been tied behind his back, which means that they must have been pressing tightly against the sides of the body, thus leaving no gap for the errant bullet to pass through without damaging soft body tissue before harmlessly hitting the ground. This analysis is strongly supported by an examination of the picture in Annex II, which depicts a model whose hands have been tied behind his back and who was positioned face down on the ground, just as Q had claimed he was. But Q’s astonishing testimony was accepted as authentic and his narrative was incorporated in all the Srebrenica ICTY judgments, with the exception of the Tolimir case. Even though Q gave evidence in that case, as well, the Tolimir Chamber did not mention him at all in its judgment. Perhaps the chamber found his story absurd; yet it did not want to break ranks with the other trial chambers by publicly saying so.

The gist of Q’s account of the massacre of Pilica is supposed to corroborate executioner Erdemović’s account. Q then waits for night to fall, and then he sneaks away from the killing field, as it is usually done in the movies.

Ahmo Hasić. There are two main points of interest in Hasić’s evidence. The first, and most glaring, is of a statistical consequences. It may be recalled that Erdemović referred to 1,200 execution victims in Branjevo and another potential 500 victims at the Cultural Centre in Pilica. While giving evidence in the Popović case, it seems that Hasić was inadequately rehearsed for his part because he let the cat out of the bag. He said that as the Serbs were bussing him to the detention facility in Pilica, he disobeyed orders to keep his head down, snuck a peek, and noticed that his group was being taken to the execution site in a convoy of seven buses,[34] which would hardly have been enough vehicles to accommodate the 1,200 to 1,700 execution victims alleged to have been taken on their final journey. Asked to estimate the capacity of each bus, Hasić put it at “50 or so.”[35] This would suggest a maximum capacity of 350 to 400 persons, which falls considerably short of the number asserted in the narrative that Hasić was enlisted by the Prosecution to corroborate.

Like Q, Hasić says that bursts of gunfire began suddenly before any command had been given, and it is not entirely clear how he managed to fall faster than the bullet flies, but he fortunately survived.[36] Then, as Hasić describes it, an extraordinary thing happened. Instead of administering the coup de grâce indiscriminately to one and all, the Serbian soldiers decided to do it the easy way: “[w]hen the bursts of fire died down, one of them asked, ‘Are there any survivors?’ ‘I survived, kill me,’” Hasić quoted one victim as saying. “So they … would go from one survivor to another and fired a single bullet to the head.” This time they were apparently unconcerned with the risk of soiling their uniforms. At that moment, Hasić says that even he toyed with the idea: “I thought about notifying them that I was alive.”[37] Luckily for him, as well as for the Tribunal, he resisted the temptation.

There seems to be no need to attempt an in-depth critique of Ahmo Hasić’s evidence concerning the execution site. It speaks for itself, and it has been quoted merely to demonstrate the kind of material that passes for evidence at The Hague Tribunal.

V

Finally, a brief review of the forensic data and its treatment by the Tribunal is in order to complete the picture.

The forensic record pertaining to the execution site in the farming field in Branjevo is straightforward. In 1996 and 1997, an international team of experts conducted exhumations on behalf of the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICTY.

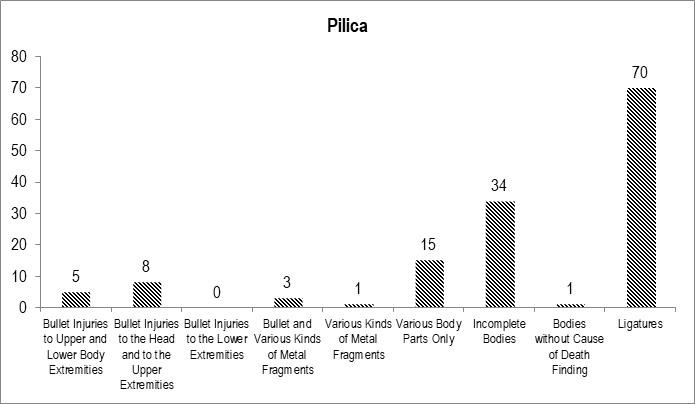

A breakdown of the contents of the Pilica/Branjevo mass grave[38]

The Pilica/Branjevo farm is notable for the number of bodies with blindfolds and/or ligatures. They number 70, or 51 % of the total number of cases examined here. That at least confirms that prisoners must have been executed there. The remainder is either body fragments or incomplete bodies. With regard to the incomplete bodies from this mass grave, it may be noted from the graph that, in addition to bullet fragments, various other metal fragments were found, as well; another portion had only bullet-related injuries; and the rest did not exhibit any injuries at all, so no cause of death could be determined. Of the fifteen cases where only a small body fragment or a few bones existed, the cause of death could not be determined in twelve.

There was a total of 137 “cases” in this mass grave, which, following the classification methodology of Prosecution forensic experts, are not the equivalent of 137 bodies. As shown in the breakdown, based on an analysis of the forensic team’s autopsy reports from this locale, forty-nine “cases” fall outside the category of complete bodies and consist of fragments or body parts. To give a precise answer to the question of how many individuals are buried in this mass grave is not an easy task. But if we take a conservative approach and deduct the fifteen cases in the “various body parts category” from the 137 “cases”, then we obtain an approximation of 122 bodies; if we rely on pairs of femur bones as the criterion, then there would be 115.

To this number we should perhaps add thirty-two cases from other mass graves that were found to be DNA-linked to Pilica/Branjevo.[39] The procedure of separately counting disarticulated body parts found in another grave may be questionable, because it could be argued that such body parts belong to the same person, most of whose remains would be found at the original burial site. But since this methodology has been accepted by the ICTY in practice, and since the addition scarcely makes material difference, we can avoid unnecessary contention by just accepting it provisionally.

Adding up 122 bodies found in the Branjevo mass grave and 32 bodies presumably also originating from Branjevo, we have material evidence pointing to at most 154 murders at that location.

Interestingly, during Radovan Karadžić’s cross examination of Erdemović, information turned up indicating that an earlier mass grave, possibly going back to World War II, may have overlapped with the Branjevo execution site.[40] This suggestion is corroborated to a limited extent by the fact that fourteen autopsy reports[41] from the 1996 exhumation demonstrate the existence of remains that have been completely skeletonized. Since the disintegration of soft tissue generally takes four to five years, it is unlikely that victims of a murder that took place a year and a half before such exhumation would have been skeletonized so quickly.

The resulting forensic picture of Pilica/Branjevo is complex. It requires an analytical approach taking into account a variety of factors. Given the strong suggestions that a crime did take place there, and that, given the great number of ligatures found there, the crime probably did involve prisoners; however, these accounts do not lend much specific support to the narratives put forward by either Dražen Erdemović or by the two purported execution survivors. Those narratives have been received sympathetically by all the ICTY trial chambers that heard them; were treated as factual evidence; and were incorporated into judgments which purport to give a true and accurate representation of what actually happened at the Branjevo/Pilica location.

VI

To summarize the results obtained so far: the primary objective is not to polemicize against the The Hague Tribunal’s manner of dealing with evidence but to illustrate it, and, in a few selected cases, to test its efficacy in empirically quantifiable terms. In a judicial setting, “efficacy” is a determination of whether a procedure assists or hinders the fact-finding process, which, therefore, either advances or impedes the administration of justice. The Pilica/Branjevo massacre was selected as a test case because it is probably the best documented of the several episodes, occurring immediately after the fall of Srebrenica, in which Muslim prisoners of war were extra-judicially executed by elements said to be associated with Serbian forces.[42] “Empirically quantifiable terms” refers to the availability of physical evidence (in this specific case, exhumed human remains and corresponding autopsy reports that describe their condition) as opposed to statements and impressions of witnesses. The latter are also potentially valuable fact-finding tools; provided, however, that the sources are credible witnesses. Even so, witness evidence is known to be fraught with the subjectivities inherent to human nature. Its reliability is strengthened by the degree to which it conforms to the material evidence. That is why a synopsis of the empirical findings resulting from exhumations conducted in the field has been presented for comparative analysis. This makes it possible to compare key foreground points in the various witness statements to a background of objective facts in order to test the former’s reliability.

Viewing the picture as a whole, it clearly cannot be said that evidence indicating a massacre had taken place in Pilica/Branjevo is entirely fabricated. It would be more accurate to say that it was manipulated, primarily in order to effect the perception of the massacre’s scale and — in conjunction with similar manipulations of other post-July 11 events that took place in and around Srebrenica — its legal characterization.

The principal percipient informant about the events that took place in Branjevo on 16 July and their scale is Dražen Erdemović. Messrs. Q and Hasić were introduced by the Prosecution merely for atmosphere, to convey from their limited personal perspectives the horror of what took place. Erdemović evidently is not a witness of truth, although he may have been present and some of the details he recounts might be accurate. But he had an ulterior motive: to get off with the lightest possible sentence and to be awarded various perquisites by the Tribunal for his cooperation as a witness. He inflates the number of prisoners, as well as the death toll, and he adjusted his account to serve prosecutorial requirements and expectations. The two “supporting actors,” witnesses Q and Hasić, simply overact their parts. If all three of them had stuck to what they had actually seen and experienced, instead of adding such transparent melodramatic flourishes and outright lies that make even a basically accurate story fall apart, we might now be in a better position to sort out what actually happened in Branjevo.

We are thus facing the enormous disparity between witness evidence, routinely given precedence by ICTY Chambers, which alleges in this case 1,200 to 1,700 murder victims in Branjevo, while evidence of corpora delicti in the field indicates a number of about 154. This yields an impressive 10:1 ratio of disproportion in the number of victims between witness testimony allegations and forensic evidence. May Tribunal sceptics really be reproached for exercising caution in evaluating the ICTY’s findings under these circumstances?

Needless to say, the assertions made by these corrupt witnesses would have had little or no impact on the proceedings if only the Prosecution had faithfully executed its obligation to test the integrity of its evidence before presenting it in court. And even if in its over-zealousness the Prosecution failed to meet its obligation, the vaunted Chamber of experienced professionals should have been sufficiently alert to detect the absurdities in the witness testimony, to exercise its prerogative to ask probing questions, and ultimately to assign it the low credibility rating that it merits.

The Defense’s duty to act with integrity when presenting evidence is clearly spelled out in the ICTY Code of Professional Conduct for Counsel Appearing before the International Tribunal (the “ICTY Code”). In Article 23, Candour Toward the Tribunal, it states:

(B) Counsel shall not knowingly:

(i) make an incorrect statement of material fact or law to the Tribunal; or

(ii) offer evidence which counsel knows to be incorrect.[43]

The same rules apply equally to the Prosecution. It so happens that The ICTY Code [Draft version] in Article [7] (5) contains an analogous provision. Prosecution counsel are enjoined to “[N]ever knowingly make a false or misleading statement of material fact to the Court or offer evidence which he or she knows to be incorrect…”[44]

So, with the benefit of hindsight, the Prosecution and the Chamber are the main points where the system of evidence breaks down at ICTY. Under a doctrine that treats the judges as discerning professionals who cannot be fooled by most kinds of trickery, which is practically tantamount to an attribution of infallibility — the Prosecution’s duty to act with integrity when presenting evidence has been essentially suspended. The Prosecution enjoys carte blanche to use the courtroom as a stage to introduce a large caste of charlatans as witnesses who are then permitted to recite their incoherent stories — steeped in horror and replete with wild misrepresentations — for the benefit of a global audience, which is far wider than the Chamber itself. Uncritical media reporting of these improbable courtroom narratives engineers public perceptions. The media generated pressure is reflected also in the judges’ reluctance to challenge defective evidence either during the proceedings or later, in their judgments. The Court’s misguided preference for flawed evidence, and its arrogant disdain for establishing facts by using time-tested judicial techniques for distinguishing fact from fiction, have been the hallmarks of Tribunal’s jurisprudence. For the ICTY, never calling the Prosecution to account for presenting evidence that verges on misrepresentation and is often plainly beyond the pale of credibility, results in a bitter harvest of widely disputed factual findings and dubious legal conclusions.

Endnotes:

[1]. Be it noted that the Srebrenica massacre has been ruled a genocide in the Krstić, Popović, and Tolimir cases before various chambers of ICTY.

[2]. NIOD Report, Part I: The Yugoslavian problem and the role of the West 1991-1994; Chapter 10: Srebrenica under siege.

[3]. Debriefing on Srebrenica (October 1995), pars. 2.20, 2.30, 2.34, 2.35, 2.38, and 2.43.

[4]. In the view of several ICTY Chambers, they were forcibly expelled.

[5]. Renaud Girard, « Bosnie: la confession d’un criminal de guerre, » Le Figaro (Paris), 8 March 1996.

[6]. For an exhaustive analysis of Erdemović’s evidence, see Germinal Čivikov, Srebrenica: The Star Witness [Translated by John Laughland], Belgrade 2010.

[7]. Erdemović, T. 150.

[8]. Erdemović, T. 150-151

[9]. The fiction at the Hague Tribunal is that it operates on a fusion of the Common Law and Continental legal traditions. It is hardly disputed, however, that in reality it is the adversarial approach of the Common Law system that predominates.

[10]. Testifying in the trial of Radovan Karadžić, under cross-examination Erdemović admitted that was the context of the bar room brawl which left him seriously injured, see Karadžić Transcript, 28 February 2012, pp. 25390-25391.

[11]. Le Figaro, op. cit. « L’ancien soldat qui rapporte ces faits a négocié avec le tribunal de La Haye. Contre la promesse d’une immunité et la possibilité de s’installer en Occident avec sa famille, il était prêt à tout dire. »

[12]. The latest iteration of this scenario was made at the Karadžić trial, T. 25374 – 25375.

[13]. See evidence at the Popović et al. trial, T. 10983: “According to my estimate, between 1,000 and 1,200.”

[14]. According to the finding of the ICTY Chamber in Blagojević and Jokić, Trial Verdict, Par. 763.

[15]. Ibid., Par. 349-350.

[16]. The Chamber accepts the demotion as a proven fact in its judgment of 29 November 1996, Pars. 79 and 92. Erdemović was initially sentenced to ten years in prison on a plea-bargaining agreement, but after he successfully challenged the basis for the agreement, is sentence was reduced to five years. He served a total of three years and a half in prison.

[17]. See document OTP file number 04230390, Order to Deploy of the Command of the Tenth Sabotage Detachment, 10 July 1995.

[18]. Blagojević and Jokić, T. 10526.

[19]. Popović et al., T. 14041.

[20]. The Tolimir Chamber held unambiguously that soldier Brano Gojković was in command, Par. 493.

[21]. 30 OTP file number 00399985-6.

[22]. Prosecutor v. Ratko Mladić, Transcript, 2 July 2013, p. 13704.

[23]. On 4 February 2016, the Serbian media reported that Brano Gojković had been apprehended and “admitted guilt for the murder in July of 1995 of several hundred persons from Srebrenica” and that as a result, “following his admission of guilt, the High Court in Belgrade sentenced him to ten years of imprisonment” (http://ba.n1info.com/a80448/ Vijesti/Vijesti/Brano-Gojkovic-osudjen-na-10-godina.html). No information whatsoever was provided about the location or the circumstances of Gojković’s apprehension. As one of the key figures in Srebrenica events, Gojković undoubtedly could have revealed much in an open trial; however, due to the application of the plea-bargain principle, he was quietly and discretely placed ad acta.

[24]. The day after the executions, Bogdanović with other soldiers allegedly took part in the clean-up operation at the Pilica Cultural Center. See Popović at al., Transcript, 10 May 2007, p. 11329.

[25]. Dom (Serbian) Cultural Center.

[26]. See Transcript in Popović et al., 10 May 2007, p. 11332-11333.

[27]. See trial judgments in Blagojević and Jokić, par. 355; Popović et al., footnote 1927; Perišić, par. 715; and Tolimir, par. 500.

[28]. He testified in various trials under different pseudonyms, but here we will use here the pseudonym assigned to him in the Krstić case.

[29]. Witness statement to the State Commission for the Compilation of Facts about War Crimes, Tuzla, 20 July 1996, p. 3. OTP file number 00950186-00950191.

[30]. Witness statement to ICTY Office of the Prosecutor, 23 May 1996, p. 4. OTP file number 00798704 -00798712.

[31]. Karadžić, T. 24158.

[32]. Statement to the BiH War Crimes Commission, 20 July 1996, p. 4.

[33]. Tolimir, T. 30419.

[34]. Popović et al, T. 1190.

[35]. Ibid., T. 1198.

[36]. Ibid., T. 1202-1203.

[37]. Ibid., T. 1203.

[38]. S. Karganović [ed.]. Deconstruction of a Virtual Genocide: An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Srebrenica. Den Haag – Belgrade 2011. Chapter VI, Ljubiša Simić: “Presentation and interpretation of forensic data (Pattern of injury breakdown” p. 101. Den Haag – Belgrade 2011.

[39]. These are: Kamenica 4, 1 body; Kamenica 9, 26 bodies; Čančari Road 11, 3 bodies; and Čančari Road 12, 2 bodies, for a total of 32.

[40]. Karadžić, T. 25387-8.

[41]. The following are the official ICTY designations of Pilica Autopsy Reports (1996) which are completely skeletonized: PLC-59-BP; PLC-61-BP; PLC-82-BP; PLC-106-BP; PLC-119-BP; PLC-123-BP; PLC-125-BP; PLC-127-BP; PLC-129-BP; PLC-131-BP; PLC-132-BP; PLC-134-BP; PLC-136-BP; PLC-138-BP.

[42]. Regular or rogue is an issue we can set aside for the moment.

[43]. http://www.icty.org/x/file/Legal%20Library/Defence/defence_code_ of_conduct_july2009_en.pdf

[44]. http://www.amicc.org/docs/prosecutor.pdf

ANNEXES

Annex II: