Momir Nikolić, assistant security officer in the Bratunac Brigade during the war in Bosnia, was indicted by ICTY for complicity in Srebrenica genocide and brought to the Hague in 2002 to face trial. He was one of several accused who chose to make a plea bargain with the Prosecution. Invariably, those who took that path were obliged to testify falsely as Prosecution witnesses in exchange for shorter and more predictable sentences. Nikolić made that Faustian bargain and the false testimony he gave in various Srebrenica trials affected subsequent judgments and greatly shaped the perception of events in Eastern Bosnia in July 1995.

Key claims on which the Srebrenica genocide narrative is based rest upon the uncorroborated evidence of sole witnesses of dubious integrity. The public have been carefully shielded from knowledge of this fact. Dražen Erdemović is a notorious example with his dubious account of Pilice executions. Dragan Obrenović invented a phone call, of which there is no record anywhere, from Zvornik Brigade security officer Drago Nikolić allegedly informing him of planned prisoner executions. Miroslav Deronjić, as part of his plea bargain with the Prosecution, implicated top Serb military and political figures in the creation of an alleged plan to exterminate Srebrenica Muslims. Another important ICTY plea-bargainer whose statements were used by the Prosecution to fill huge factual gaps in its case was Bratunac Brigade security officer Momir Nikolić. His signed „Statement of Facts and Acceptance of Responsibility“ given to the Prosecution is attached below.

When in 2003, several days before his trial was to begin, Nikolić decided to make a deal with the Prosecution in return for a predictable and lighter sentence, like other accused entering into a plea bargain agreement he committed to testify in support of the Prosecution case. There were two critical areas case where Nikolić could help the Prosecution. The first was the Fontana Hotel meetings held in Bratunac on July 11 and 12, 1995, where the Prosecution claimed the Serbian leadership formulated a plan to exterminate Srebrenica Muslims. The other area where the Prosecution case was weak but Nikolić’s testimony could help immensely was in augmenting the number of alleged genocide victims. At the Krstić trial, which had ended slightly over a year before, the Prosecution tried to make up for the disappointing results of exhumations carried out by its own forensic experts by alleging that most victim bodies were actually missing because they had been reburied elsewhere in order to cover up the prisoner executions. The evidence presented for such a scenario was so thin, however, that even the Chamber was unwilling to lend it much credence.

Momir Nikolić’s expressed willingness, in return for a lighter sentence, to testify that he had personal knowledge of the reburial operation and had participated in it was therefore a major development for the Prosecution.

The Fontana Hotel meetings and their implications

According to the Prosecution, the “genocidal plan” was agreed on at three meetings held by the Serbian political and military leadership at the Fontana Hotel in Bratunac. The alleged consensus of those meetings was that the Srebrenica Muslim community would be physically destroyed. Momir Nikolić offered his incriminating account of those meetings, for two of which he was present in the capacity of security officer for the Bratunac Brigade. He essentially confirmed ICTY Prosecution’s claim that the main topic was planning for the extermination of Srebrenica Muslims.

Testifying in the Blagojević and Jokić trial, Nikolić disclosed how he became privy to the important information which he was sharing with the chamber. Being greatly inferior in rank to the meeting participants (for Nikolić’s rank, see Transcript, p. 1652-57; for the ranks of meeting participants, see Blagojević and Jokić Judgment, Par. 150), Nikolić refrained from claiming that he was physically at the conference table. He said that he was sitting in one of the adjoining rooms “from where he could overhear” the conversation because the door was open (Judgment, ibid., Par. 154; Transcript, p. 1667). As for the alleged plan to expel the population and execute prisoners, Nikolić testified that he learned about it from another officer after the third and last of the Fontana Hotel meetings (Blagojević and Jokić, Judgment, ibid., Par. 161). He did not claim to have “overheard” these specific decisions actually being made. There is no corroborating evidence from any other source that such information was ever passed on to Nikolić after the meetings.

The benefit the Prosecution would derive from Nikolić’s testimony can be seen by comparison with where the Krstić Chamber stood on this issue, as reflected in its Trial Judgment in 2001.

In Prosecutor v. Krstić, Par. 126-134 and Par. 573 of the Trial Judgment (and also Par. 84, 85, and 91 of the Appellate Judgment) the importance the Chambers attached to these Fontana Hotel meetings and how limited was the information it had about them up to that point is clearly shown.

Par.73 of the Krstić Trial Judgment is certainly an example of how an ICTY Chamber can still draw its preconceived conclusions even in a factual vacuum and regardless of the availability of specific evidence: “The Trial Chamber is unable to determine the precise date on which the decision to kill all military age men was taken. Hence it cannot find that the killings committed in Potočari on 12 and 13 July 1995 formed part of the plan to kill all the military aged men. Nevertheless, the Trial Chamber is confident that the mass executions and other killings committed from July 13 onward were part of this plan.”

The Appellate Chamber in Krstić admitted that it lacked specific evidence of what was discussed at the meeting in the Fontana Hotel, but it stated its belief, in light of the totality of the evidence (the operative phrase in Par. 91 being: “it is reasonable to infer…”), that the meeting was an ideal opportunity to formulate such a plan for the “genocidal operation.” It then proceeded on the theory that what it assumed is what actually had happened (Prosecutor v. Krstić, Appellate Judgment, Par. 91-94).

The Prosecution clearly sought to postulate the meetings at the Fontana Hotel as the Serbian equivalent of the Wannsee Conference in 1942, where Hitler and his staff decided to exterminate European Jews. Its neat parallel is spoiled, however, by the fact that for Wannsee we know who was in attendance, the agenda, and the decisions that were made. That was for the most part admittedly missing in the case of the Fontana Hotel meetings, based on the evidence presented to the Krstić Chamber. It is for that reason that Momir Nikolić’s claim, as an alleged eyewitness, that the expulsion and extermination of Srebrenica Muslims were, in fact, the principal subject of discussion at the Fontana Hotel bolstered the Prosecution’s case significantly, notwithstanding this witness’ serious credibility issues. Reasoning that in the Krstić case had to rest for the most part on assumptions, because of Nikolić’s cooperation with the prosecutor could now be repackaged to appear supported by direct evidence.

Nikolić’s reburial operation claims

The Fontana Hotel proceedings, where other potential witnesses were also in attendance whose testimony might have to be considered, was not where Nikolić made his principal contribution as a Prosecution witness. He became a pivotal (and sole, as it also conveniently turned out) Prosecution witness when he agreed to testify about his personal knowledge of and participation in the alleged reburial operation. The Prosecution was indeed struck by good fortune when shortly after the Krstić trial, where only paltry forensic evidence of about 2,000 victims could be produced, Nikolić volunteered his sensational-sounding insights. On the issue of reburials, the Krstić trial judgment remained fundamentally non-committal. While absolving defendant Krstić personally of knowledge or involvement in the alleged cover-up, the Chamber also admitted that evidence that reburial even took place was at that point scarce. While claiming in the Krstić judgment that there was – uncited – forensic evidence of a “concerted effort to conceal the mass killings by relocating the primary graves,” the Chamber also conceded that “the Prosecution presented very little evidence linking Drina Corps Brigades to the reburials and no eyewitnesses to any of this activity were brought before this Trial Chamber.” (Krstić Trial Judgment, par. 257)

That was a remarkable critique, almost a rebuke to the Prosecution case. In plain language, it meant that at that point the case for reburials stood essentially unproved, even from the perspective of the prosecution-friendly trial chamber. Momir Nikolić’s timely appearance in time for next Srebrenica trial [Blagojević and Jokić] as just the missing eyewitness was critical to fill in the missing details. It also occurred at a strategic moment to give the Srebrenica story a new lease on life. A few years later the problem of missing bodies was solved more efficiently by means of DNA matches, but that would not have been possible but for the Tribunal’s prior acceptance of Nikolić’s reburial claims.

The contrast in the treatment of reburials in the Krstić trial judgment and in the succeeding Blagojević and Jokić trial is striking and is owed entirely to the plea bargain and subsequent testimony of Momir Nikolić.

In Par. 383 of the Blagojević and Jokić trial judgment, cooperating witness Momir Nimkolić is cited as the source implicating the Republic of Srpska Army (VRS) Main Staff in the reburial operation. Momir Nikolić is cited as having claimed that he was tasked by his superiors with organizing the reburial operation in the area of responsibility of the Bratunac brigade. (Blagojević and Jokić, Transcript, p. 2355)

In Par. 384 of the same judgment, Momir Nikolić’s testimony about his personal role in the reburials is recalled. Nikolić is quoted as admitting that a “large number of people and vehicles were involved” in the endeavour he was describing (Ibid., Transcript, 2294-96). In Par. 385, Nikolić is quoted as claiming that he took part in exhumations in the locality of Glogova “in September or October 1995”. Glogova is located on flat terrain where concealment of a large-scale digging operation would be difficult. There is no reference to aerial photos of the alleged exhumation in Glogova, nor is there any corroborating testimony of civilian witnesses from the surrounding villages.

As could be expected, in Par. 389 of the Blagojević and Jokić judgment, the testimony of another cooperating witness, Zvornik Brigade chief of staff Dragan Obrenović, is quoted concerning the exhumation and reburial process in the Zvornik Brigade area of responsibility. [1]

To sum up, it was Nikolić’s bogus and completely uncorroborated evidence that transformed the remains of what were probably 28th Division column battle casualties sustained as it was making its way from Srebrenica to Tuzla through Serbian ambushes, into a huge reserve of body parts ostensibly of genocide victims. Later on, they were supposedly even individually identified by DNA matching conducted on a massive scale.

Momir Nikolić’s credibility

Nikolić’s performance as a prosecution witness in ICTY Srebrenica trials was marred from the beginning by credibility problems. There is one peculiarity in Nikolić’s case that sets him apart from other ICTY plea bargain witnesses. In order to impress the prosecution with his willingness to cooperate, the overzealous Nikolić lied by taking responsibility for several murders that, as a diligent defense attorney eventually established, he did not commit.[2] Liu Daqun, the sentencing judge, initially rejected Nikolić’s dishonest guilty plea only to later reverse himself and accept it, but in the judgment Nikolić’s evidence was excoriated for “lack of candor.”[3] In its submission to the Popović Chamber it was the Prosecution that proposed that Nikolić’s “evidence should be relied on only when corroborated.”[4] That sensible stipulation was ignored in Nikolić’s subsequent appearances as Prosecution witness. At ICTY, apparently, the ancient adage falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus (“false in one thing, false in everything”) never entered its judicial practice.

In his eagerness to please, Momir Nikolić rendered uniquely valuable services as a witness for the ICTY Prosecution: he seemed to pop up anywhere a gap in the evidence needed to be filled. For the Prosecution, he is the principal source of evidence for the alleged reburial of executed prisoners in secondary and tertiary mass graves, allegedly undertaken by Serbian forces to conceal evidence of the mass crime.[5] But Nikolić also claimed that he was in Potočari, so he could apprise the court of the details of the Serbian “ethnic cleansing operation” during which about 20,000 Srebrenica residents — women, children, and elderly — were evacuated by Serbian authorities away from the combat zone to safety in Kladovo, the nearest town controlled by the ARBIH.[6] Nikolić also just happened to be in the company of General Ratko Mladić in Konjević Polje. He testified in Mladić’s trial that Mladić ran a finger across his neck in a throat-slitting gesture in response to Nikolić’s question what fate was awaiting the prisoners. This gesture supposedly left no doubt about the General’s intentions.[7] Predictably, Nikolić, a natural Johnny on the Spot, was also in the proximity of the Kravica Warehouse at just the right time to offer his first-hand observations to the court of what happened there. Interestingly, Nikolić actually went above and beyond the call of duty in his 2003 confession to affirm “that he had ordered the executions at Kravica Warehouse.”[8] He later recanted this confession, which never was corroborated by any other evidence but, in the view of ICTY chambers, this tenuous connection apparently sufficed to validate this bearer of false witness to testify on other aspects of the Kravica affair.

The oddly smug comment made by the Chamber in the Karadžić Trial Judgment, Par. 5059, after recounting numerous prevarications on Nikolić’s part, is a striking indication of the importance that the Tribunal attaches to this witness’ testimony: “Accordingly, the Chamber is satisfied that his inconsistency was not inspired by any insidious desire to mislead the Chamber. In its final analysis, the Chamber is convinced that the aforementioned inconsistencies in no way affect Nikolić’s overall credibility, nor do they justify a rejection of his evidence. In reaching this conclusion, the Chamber also paid particular attention to the fact that the consistency of the witness remained undiminished throughout his various statements and testimonies in respect of other matters.”

Similarly, the Popović Chamber also admitted that it was under no illusion that Nikolić ingratiatingly confessed to crimes he did not commit and gave false testimony in order to secure what he considered an advantageous plea agreement with the ICTY prosecutor.[9]

In Footnote 73 of its judgment, the Popović Chamber concedes that “the Trial Chamber which sentenced Momir Nikolic was strongly critical of him, finding that his testimony was evasive in several instances and that he was not fully forthcoming. [Nikolić Sentencing Judgement, para. 156.] However, the Appeals Chamber which reviewed these comments in the context of assessing mitigation through cooperation found that the Trial Chamber had failed to provide a reasoned basis for its conclusions in this respect and had thus committed an error. [Nikolić Sentencing Appeal Judgement, paras. 98–103.] In the trial of Blagojević and Jokić, Momir Nikolić testified after entering into a plea agreement but prior to sentencing. In these circumstances and given that he was an accomplice, the Trial Chamber exercised caution in assessing his evidence, accepting it in some instances and rejecting it in others. See Blagojević and Jokić Trial Judgement, paras. 212, 262 [where the Trial Chamber accepts Momir Nikolić’s evidence because of its self-incriminatory nature], para. 472 [where the Trial Chamber does not accept uncorroborated evidence by Momir Nikolić on matters that bear directly on Blagojević’s knowledge]. See also Blagojević and Jokić Appeal Judgement, paras. 80–83 [holding that it was not unreasonable for the Trial Chamber to accept certain parts of Momir Nikolić’s evidence, and to reject others].”

So, clearly, the falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus principle does not operate at ICTY. Chambers encourage each other to pick and choose bits of testimony of witnesses they recognize as basically false, as long as these bits are suitable to prove some point that the Chamber is interested in establishing. The reburial operation is one such key point in the Srebrenica narrative.

Nikolić’s importance to ICTY as a witness was apparently such that in certain matters his credibility had to be vigorously defended from all challenges. That was reiterated by the Mladić Chamber in Par. 2475, Vol. III, of its Trial Judgment:

“The Defence submitted that the testimony of Momir Nikolić with regard to the Hotel Fontana meetings is not credible because, inter alia, he downplayed his role in the meetings, which is in contrast to the evidence of Boering who testified that Nikolić was ‘in charge of everything at that point’. The Trial Chamber notes, however, that the evidence of Boering cited by the Defence relates to meetings with Nikolić other than the Hotel Fontana meetings alleged to have taken place on 11 and 12 July 1995. The Trial Chamber, therefore, finds the Defence submissions in this regard to be unpersuasive.”

Many other witnesses were also mentioned in the Mladić judgment in a variety of contexts, but Nikolić is the only one for whom the chamber was prepared to go to battle in order to ensure his credibility. It can easily be understood why, from their point of view. What Erdemović was to the Pilica story, Nikolić is to the Hotel Fontana and more importantly reburial accounts (the latter unsupported by any independent evidence whatsoever). In that volume of their judgment Nikolić is cited by the Chamber 381 times, signalling rather clearly their great reliance on what he had to say.

How credible is Nikolić’s reburial evidence?

The fact that Momir Nikolić is the sole witness to what he has described as a complex operation involving the exhumation, physical transfer, and reburial of hundreds of tons of human flash makes his account intrinsically suspect. What he has described on the stand obviously is an operation that could not have been performed by one person. To have occurred, it must have involved many assistants and a logistical infrastructure of considerable complexity. Nikolić was never asked and (unlike Erdemović, for instance) he never disclosed the names of any assistants during the alleged reburial operation. What he has testified to is essentially an inherently improbable (perhaps „impossible“ is a better word) one-man show.

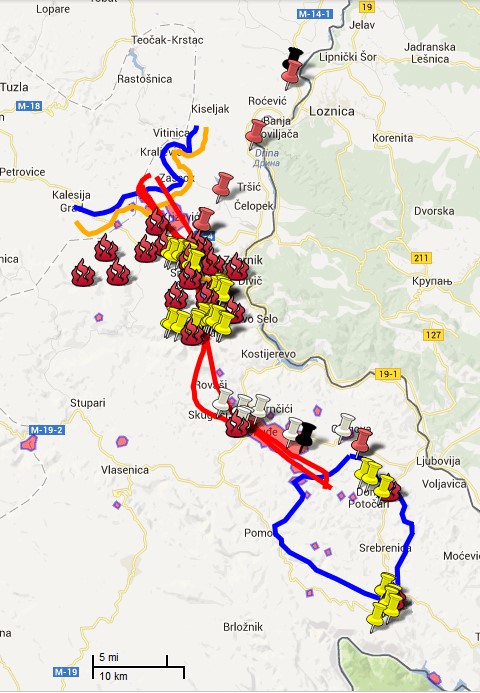

There is a more sensible explanation for the proliferation of human remains in areas indicated by Nikolić as reburial sites. They are located conspicuously along the path of retreat from Srebrenica to Tuzla of the 28th Division column and in proximity to locations where there was combat activity between elements of the column and the Serbian troops ambushing it. The map produced by our associate Andy Wilcoxson (an amalgamation of several maps previously admitted into evidence by various ICTY chambers[10]) shows the close proximity of most of the so-called “secondary burial sites” to the path of the column, generally to within one or two miles. That strongly suggests that these were in fact primary burial sites that originated not from executions which took place at some distance but from the ground-clearing operation in the immediate vicinity, a legitimate activity that follows a battle. They were later relabelled “secondary” and even “tertiary” gravesites in conformity with Nikolić’s unsubstantiated reburial claims. The objective was to increase the quantity of human remains that could be misrepresented as genocide victims. As the map that follows shows, the geographical distribution of the so-called “secondary” mass graves indicated by Nikolić as reburial sites is such that they more plausibly contained the bodies of the column’s combat casualties instead of execution victims. In his capacity as the Bratunac Brigade security officer, it is reasonable to assume that Nikolić was aware of the locations of the mass graves where 28th Division column casualties were deposited upon the completion of the ground-clearing operation, so when he decided to become a prosecution witness he was in a position to point them out. On the strength of Nikolić’s testimony, those sites were converted by the Prosecution to „secondary graves.“ The human remains found there were uniformly reclassified as belonging to „genocide victims.“ They furnished the grist for the alleged massive DNA identifications that followed.

On this map, the yellow markers denote secondary graves and flames denote places where combat took place. Red markers denote primary disturbed graves where remains were taken from, and white markers denote primary undisturbed graves where no remains were taken. Red lines show the path taken by the column. The blue lines show the enclave boundary and the Bosnian Army’s forward lines around Tuzla. The orange lines are the positions held by the Bosnian-Serb army. The red shaded areas are where surface remains have been found. Wilcoxson comments: “As can be seen from the map, the secondary graves are located very close to the enclave boundary where fighting took place between July 6th when the Bosnian-Serb Army first attacked the enclave until July 11th when Srebrenica fell, or in areas where the column was known to have fought with the Bosnian-Serb Army on its trek towards Tuzla. Put simply, the ‘secondary’ graves are located in precisely the area where one would expect to find combat casualties associated with Srebrenica.”

No satellite or aerial platform imagery of the alleged reburial operation was ever produced in court and amongst the many who must have assisted Nikolić in this endeavour – if it had ever taken place as he described it – not a single individual was called to court in any Srebrenica trial to testify under oath in corroboration of Nikolić’s claims.[11]

False witness Momir Nikolić’s account of the Fontana Hotel meetings and alleged reburials is an important building block of the false Srebrenica genocide narrative. It is a vivid illustration of the substandard quality of the evidence put forward by ICTY Prosecution and relied upon by the Chambers to draw monumental conclusions, including the commission of genocide. Once a comprehensive re-examination of ICTY’s legacy, unencumbered by politically motivated pressure to assent to obvious falsehoods, inevitably takes place, The Hague Tribunal and its judgments will live in infamy.

Endnotes:

[1] Dragan Obrenović was originally to be tried alongside Nikolić, Blagojević, and Jokić for complicity in Srebrenica crimes. Upon learning that Nikolić had concluded a plea bargain a few days before the trial was scheduled to begin, Obrenović informed the prosecutor that he had decided to do the same and followed suit.

[2] See IWPR ICTY, 3 October, 2003, Sporan kredibilitet svedoka maskara u Srebrenici [Credibility of Srebrenica Massacre witness disputed], https://iwpr.net/sr/global-voices/sporan-kredibilitet-svedoka-maskara-usrebrenici

[3] See Momir Nikolić, Trial Judgment, Par. 156.

[4] See Popović Sentencing Judgment, Par 49. In assessing this witness’ credibility, the Popović Chamber took the further unusual step of advising a “cautious and careful approach when considering the evidence of Momir Nikolić” (ibid., Par. 51).

[5] See Momir Nikolić, Statement of Facts and Acceptance of Responsibility, https://www.legal- tools.org/uploads/tx_ltpdb/NikolicM._ICTYTCPleaAgreement_Statement offacts_06-05-2003_E_05.htm

[6] Ibid.

[7] See Nezavisne Novine (Banja Luka), 3 June 2013, http://www.nezavisne.com/novosti/bih/Momir-Nikolic-Mladic- nagovijestio-ubijanje-zarobljenika-u-Srebrenici/194724

[8] Popović et al., Trial Judgment, Footnote 72.

[9] See Popović trial transcript, 23 April 2009, page, 33090-33094

[10] Krstic exhibit P00159 (Map of enclave boundary, and Route taken by column according to prosecution witness R), Popovic exhibit P02996 (Map showing location of primary and secondary graves), Krstic exhibit P00002 (Map produced by Bosnian Serb Army showing route taken by column, Confrontation lines, Where the VRS entered the enclave, and where the Bosnian Serb Army had its positions), Krstic exhibit P00549 (Map produced by Richard Butler showing enclave boundary and locations where combat took place on 14 July 1995), Krstic exhibit P00613 (Map produced by Richard Butler showing enclave boundary and locations where combat took place on 15 through 16 July 1995), Map produced by the Bosnian Government in cooperation with the ICMP showing locations were surface remains were found.

[11] The Blagojević and Jokić chamber seem to suggest a sensible awareness that reburials must have involved more than a single individual where they find that “a plurality of persons participated in the capture, detention, execution, burial and reburial” of prisoners. (Trial Judgment, Par. 720)