[Testing the Pilica Massacre Narrative. The paper that follows was read by Stephen Karganovic at the XII International Law Association meeting in Tara, Serbia, 5 – 9 June 2013. It focuses on some of the evidentiary issues that arise in relation to proving key aspects of the Srebrenica massacre. We recommend it to our readers on its own merits, but also as a response to Srebrenica genocide advocates whose best argument seems to be that what has been confirmed in ICTY judgments acquires automatically the status of sanctified truth beyond the pale of permissible inquiry or further discussion. A thorough analysis of ICTY judgments with attention to the sort of evidence that has been admitted is long overdue. When scholars finally do get around to it, the results are bound to be shocking. The article that follows, with a rather narrow focus on the evidence that was uncritically admitted by several chambers in relation to the goings on at the important massacre locale of Pilica-Branjevo, is a foretaste of what a comprehensive study of this aspect of the Tribunal’s procedures would reveal.]

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia [ICTY] has mostly been exempt from the wide ranging and close critical scrutiny that a conceptually new (and ad hoc, at that) institution, with pretensions of dealing with some of the most important legal issues, should have been subjected to. That is not to say that it has enjoyed nothing but acclaim and that critical analysis of its performance has been entirely absent. But if it was designed to serve as a laboratory to test procedures and principles prior to the establishment of a permanent international body along similar lines, as has evidently happened with the founding of the International Criminal Court [ICC], it must be said that on the whole its practices have received one-sided endorsement, even if some reservations have been expressed about certain aspects of its work.

As the higher phase of ICTY, ICC obviously is now not just here, for better or for worse; its very establishment sends the implicit message that ICTY essentially did a good job and that we can now benefit from its experience and move forward. This conclusion is suggested so compellingly that it almost discourages going back to reexamine some dubious facets of ICTY’s performance that are incorporated into the “higher phase” only at grave peril for the integrity of international justice.

I.

The concept of evidence, in the broadest sense, as applied in the practice of the Hague Tribunal surely requires far more discussion and analysis than it has so far received. The way evidence is defined, presented, and handled is fundamental in court procedures and in criminal cases it is a matter of particular significance. If a judicial system operates with an erroneous concept of evidence, this is not an ordinary and easily curable error but a fundamental deficiency that ultimately infects the entire operation. If evidence is improperly received and assessed, confidence in the integrity of the entire judicial process – including its final outcome, the verdict – will be substantially undermined.

We propose to test the way in which evidence, broadly understood, is treated by the Hague Tribunal by focusing on the massacre in the locality of Pilica— Branjevo as a case study. This massacre was part of a series of similar episodes which occurred over a week’s time after the fall of Srebrenica on 11 July 1995, said collectively to constitute the Srebrenica massacre in the final stages of the Bosnian war.[1]

The selection of Pilica—Branjevo (generally referred to as Pilica for short, because that is where prisoners were assembled prior to execution, while nearby Branjevo is the location of the field where the killing took place) was made deliberately for its paradigmatic value. The principal witness, Dražen Erdemović, who ultimately signed a plea agreement with the Prosecution obligating him to testify in all Srebrenica related trials, has told his story with greater or lesser consistency and persuasiveness in a number of statements and legal proceedings. There are also two alleged survivors of the massacre, a Protected Witness we shall call Q because that was his pseudonym in the Krstić trial and Ahmo Hasić, who testified variously under his real name and under pseudonym in several trials. Finally, to round off the picture, we shall look at the forensic evidence from the place of execution to see how the witness evidence produced by the Prosecution tallies with it.

II.

The basic answer, in the present phase of the Western legal tradition at least,[2] to the questions of what constitutes probative evidence and what are the proper standards for evaluating it is not a genuinely disputed issue so a detailed theoretical introduction will not be required. Nevertheless a brief outline of fundamental principles of evidence would probably be useful.

Probative evidence is generally described thus: “When a legal controversy goes to trial, the parties seek to prove their cases by the introduction of evidence. All courts are governed by rules of evidence that describe what types of evidence are admissible. One key element for the admission of evidence is whether it proves or helps prove a fact or issue. If so, the evidence is deemed probative. Probative evidence establishes or contributes to proof.”[3] Furthermore, “Probative facts are data that have the effect of proving an issue or other information. Probative facts establish the existence of other facts. They are matters of evidence that make the existence of something more probable or less probable than it would be without them. They are admissible as evidence and aid the court in the final resolution of a disputed issue.”[4] Evidence is said to have probative value when it “is sufficiently useful to prove something important in a trial.”[5]

It is also a settled principle that probative evidence “that is otherwise admissible may still be excluded if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading the jury.”[6] A fortiori, we might add, about evidence characterised by dubious probative quality. The point about “unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading the jury” is particularly pertinent to Hague Tribunal. It operates with a panel of judges, of course, not a jury, but figuratively international public opinion acts informally as the jury in ICTY’s proceedings. So in that sense the issues of unfair prejudice and confusion that could arise from the airing of improper evidence in front of a conventional jury may still appropriately be raised. The Tribunal takes a position not completely unlike that of ancient Greek courts which operated their trials “at large” and were reluctant to exclude as irrelevant anything that could remotely be deemed evidence. It is the view of the Hague Tribunal that any hearsay, double or even triple, any scrap of paper with virtually anything written on it with the remotest bearing on some aspect of a case, any copy of any purported document even without an original to back it up, may be admissible without impairing the administration of justice because the Chamber are composed of experienced professionals who, presumably unlike an Athenian mob, are superbly qualified to separate the wheat from the chaff and make the proper assessment.

There is finally the closely related but somewhat broader concept of PROOF which refers to “[T]he establishment of a fact by the use of evidence. Anything that can make a person believe that a fact or proposition is true or false. It is distinguishable from evidence in that proof is a broad term comprehending everything that may be adduced at a trial, whereas evidence is a narrow term describing certain types of proof that can be admitted at trial.”[7] There may be sufficient proof that an event happened but nevertheless insufficient evidence to show that it occurred in a specific way or that criminal liability for it may be imputed to a specific party.

III.

What happened in Pilica? A brief and relatively uncontroversial recital of the basic facts is in order.

On 11 July 1995 Serbian forces completed a successful offensive and shut down the then protected enclave of Srebrenica. Under an agreement signed in April 1993 the enclave was supposed to be demilitarised in return for halting a Serbian military operation that threatened to defeat forces within it loyal to the Sarajevo authorities. Before April 1993 forces from Srebrenica conducted a widespread and systematic campaign against Serbian villages and settlements in the area that in the 2002 Dutch Government NIOD Report is said to have impacted “estimated between 1,000 and 1,200 Serbs [who] died in these attacks, while about 3,000 of them were wounded… Ultimately, of the original 9,390 Serbian inhabitants of the Srebrenica district, only 860 remained…”[8] Following the April 1993 truce agreement, the demilitarisation provision was openly ignored, a fully armed 28th Division of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina remained in control of the enclave, and attacks, ambushes, and provocations from Srebrenica against surrounding Serbian settlements continued unabated.[9]

Under conditions that incited strongly to revenge, in July 1995 Serbian forces occupied Srebrenica enclave, transported[10] about 20,000 mostly female, elderly and underage inhabitants safely to Muslim-held territory, and had numerous armed clashes with a mixed Muslim military/civilian column estimated to number between 12,000 and 15,000 males who were conducting an armed breakthrough from Srebrenica toward Muslim lines near Tuzla. In the process, many members of the column were killed in combat; a number of others were captured. Of those captured, some were transferred to a prisoner-of-war camp and ultimately exchanged; a number of others were summarily executed by a possibly rogue outfit called 10th Sabotage Detachment, to which Prosecution witness Dražen Erdemović belonged.

Insofar as Erdemović’s account of events is concerned, on 16 July 1995 some of the Muslim prisoners, alleged by Erdemović to have numbered about 1,200, were brought from a detention center in Pilica to a farm field in nearby Branjevo. Between approximately 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. they were executed by a firing squad of eight of which he was a member. A further 500 that remained in Pilica at a different location were executed later that afternoon by another group.

In March 1996 Erdemović contacted the media and the Tribunal, alleging pangs of conscience but also expressing the hope that in return for becoming a cooperating witness he would be accorded immunity from prosecution and resettlement with his family in a Western country.[11]

The other allegedly percipient witnesses to the Pilica massacre are Protected Witness Q and Ahmo Hasić, who has testified with and without protective measures. Both claim lucky escapes from the execution site on 16 July 1995.

Finally, some forensic evidence about what may have taken place on the farm field in Branjevo shall be reviewed as well.

IV.

The Dražen Erdemović narrative.[12] The Prosecution of the Hague Tribunal has frankly admitted that before Erdemović’s transfer to ICTY by Yugoslav authorities on 30 March 1996 (that is to say, nine months after Srebrenica) it knew nothing of the important Pilica massacre,[13] which eventually became the relatively best documented episode in the series of mass prisoner executions making up the alleged Srebrenica genocide. At Erdemović’s trial in the Hague on 19 November 1996 (a year and four months after the Srebrenica events charged in the indictment) ICTY Chief Investigator in charge of Srebrenica, Jean-René Ruez, said that even at that late stage Erdemović was still the Prosecution’s only source about the major killing operation that allegedly occurred in Pilica.[14] So presumably he must have had some important and very probative things to say. His evidence should, therefore, be crucial to sorting out a major episode in an interconnected series of crimes said to amount to – genocide.

This is all well and good, but for the Prosecution proper conduct includes a good faith effort to verify allegations intended to be used as evidence, not just putting forward any uncorroborated assertion as long as it happens to support the Prosecution case. In the adversarial system[15] the Prosecutor’s obligation as an “officer of the court”, simply put, is to check his facts before presenting them to the Chamber to make sure that his version of events is internally consistent and credible on its face at least. To what degree have these requirements been met in the case of the cooperating witness Dražen Erdemović?

To start with, the manner of his appearance in the Srebrenica controversy should have rung some alarm bells. On 3 March 1996, while recuperating in Serbia from wounds received in a shootout with another member of his unit, possibly over the division of post-massacre spoils, Erdemović invited French journalist Arnaud Girard and his American colleague Vanessa Vasić-Jeneković to hear his dramatic revelations about Srebrenica. The interview resulted in a long story in Le Figaro of 8 March 1996. The key portion of the interview, with a bearing on Erdemović’s motives, which should have aroused the critical curiosity of the media figures present as well as the ICTY Prosecutor and Chamber, is this:

“The former soldier who has reported these facts has been negotiating with the Tribunal in the Hague. In return for the promise of immunity and the possibility of resettling in the West with his family, he is ready to tell all.” [16]

So right at the outset it should have been clear to all the interested parties that if not completely corrupt Erdemović’s motives were at least mixed. In addition to salving his conscience (if we are to give him the benefit of the doubt on that score) there was also clearly present the motive of restarting his life elsewhere far from the reach of his querulous co-perpetrators and, even more importantly, with immunity from prosecution for the horrendous crimes he was describing and admitting. Quid pro quo is something he obviously had on his mind and he signaled it from the start. So the first logical question that a careful investigator and professional finder of fact would ask is: to what extent might those motives have colored, influenced, or enhanced his narrative to fit the expectations of those from whom he was expecting refuge and immunity?

The general picture of the executions at Branjevo has been consistent to the extent that witness Erdemović has repeated in several trials that the process began around 10 to 11 a.m. on 16 July and that it was over by 3 p.m. or a bit later the same day, and that prisoners were shot in groups of ten.[17] The central claim which makes this witnesses’ evidence vitally important to the Prosecution is his estimate that in that space of time (about five hours) Dražen Erdemović and seven other members of an execution squad drawn from the Tenth Sabotage Detachment shot, by his estimate, between 1,000 and 1,200 Muslim men captured by Serbian forces after the fall of Srebrenica a few days earlier.[18] While it is clear that demonstrating that up to 1,200 Srebrenica victims were shot at a single location would put the Prosecution considerably closer to proving the cold blooded murder of 8,000 prisoners, if we were to examine critically the mathematical feasibility of Erdemović’s claim some serious questions would immediately be apparent.

Five hours is 300 minutes, and 1,200 prisoners is 120 groups of ten. Dividing 300 minutes, which is the period of time the execution lasted according to this witness, by 120 groups we get about 2,5 minutes for each group to walk the 100-200 meters from the bus to the execution site, to throw their IDs and valuables on a pile, to be shot, and then finally for a Serb soldier to check for survivors and to finish them off before the next group of ten is brought to go through the same routine . How likely is this scenario in the time frame indicated by Erdemović? For comparison, a similar massacre said to have taken place in nearby Orahovac [19] involved the execution of 1,000 prisoners, or slightly less than the top figure alleged by Erdemović. Oddly, the Chamber there concluded that the Orahovac execution started on 14 July 1995 in the afternoon and lasted all evening and into the morning of the following day, 15 July, ending finally at 5 a.m. While the same Blagojević and Jokić Chamber validated Erdemović’s chronologically tight Branjevo narrative[20] it apparently failed to notice the incongruity of that with its other findings in the same judgment about analogous events in Orahovac. The Chamber there sensibly gave the executioners thrice as much time to perform a task of similar magnitude and complexity. In Branjevo, they must really have been quick on the draw.

But mathematical issues are not the only questionable aspects of witness Erdemović’s report about what happened in Branjevo. Apparently, Erdemović had taken care to portray his role in the killings in a light he thought most likely to minimize his responsibility. He testified on various occasions that he held the rank of sergeant in the Tenth Sabotage Detachment, the unit from which the killers were drawn and that in 1994 he joined the outfit with that rank. But he claimed that in April 1995 he was demoted to the rank of a simple soldier by his superiors for an infraction he committed, conveniently just months before the July massacre in which he admitted having taken part. The demotion is of some importance in his narrative[21] because he builds an image of himself as an unwilling executioner, almost a conscientious objector, who grudgingly goes along and – by his own admission – shoots 70 to 100 prisoners in Branjevo because as a simple soldier he was threatened with being executed himself if he refused. We know that since Nurnberg “following orders” has not been a valid excuse for participating in atrocities; however Erdemović is not a lawyer but an unemployed locksmith so as a layman he may have been uninformed on this point. He just tried to do what he thought best to minimize his own liability, though an alert Prosecution and Chamber would have wondered how this comports with his insistently proclaimed expressions of repentance.

They had plenty of evidence before them to make them wonder. For one thing, in commander Milorad Pelemiš’s 10 July 1995 order for the unit to join battle in Srebrenica, Erdemović is unambiguously listed as a “sergeant”[22] at a time he claimed he was a simple soldier. Moreover, his superior in the chain of command, Col. Petar Salapura in his own evidence flatly contradicted Erdemović’s claim of demotion.[23] The claim was also debunked by Dragan Todorović, the unit’s logistics officer who knew Erdemović and his status very well.[24] These credible denials that Erdemović was a lowly soldier at the time he participated in the massacre assume additional weight in light of his further claim – which really strains credulity – that another simple soldier, Brano Gojković, was actually in charge of the execution squad in Branjevo although one of the Tenth Sabotage officers, Lt. Franc Kos, was also present among the executioners and was presumably taking orders from soldier Gojković.[25]

Further concerning the goings on at the execution site in Branjevo, Erdemović also reports that when in the afternoon the killing was over, the same lieutenant-colonel who brought them there in the morning and then left now reappeared and communicating with soldier Gojković, who we already noted was supposed to be in charge, announced that locked up in another facility in Pilica there were an additional 500 prisoners who also needed to be shot. Gojković then went over to Erdemović and conveyed that order. This time Erdemović responded that he was tired of shooting and refused the order in spite of being a mere soldier, and he no longer claims that he was threatened with death for his disobedience. The high ranking officer and Gojković then ordered another group of soldiers to perform that task, still ignoring the presence nearby of Lt. Kos who presumably should have been more suitable as the lieutenant-colonel’s interlocutor if we go by the normal military chain of command.

Lack of clarity about who was in charge at the execution site is compounded by the Prosecution’s evident desire to link Serbian supreme military commander, General Ratko Mladić, as directly as possible to the commission of the crime. From the prosecutorial point of view, that is perfectly understandable and legitimate. One would think, however, that the concept of Command Responsibility, long settled at the Tribunal, would be a sufficient legal mechanism to accomplish that purpose. But apparently it is not, in the Prosecution’s view. So at the Milošević trial the Prosecution produced a document purporting to be Dražen Erdemović’s Enlistment Contract when he joined the Tenth Sabotage Detachment.[26] The main feature of this otherwise unremarkable document is what appears to be the signature of “Colonel-General Ratko Mladić” in the lower right hand corner on p. 2 of the Contract. Underneath Mladić’s purported handwriting is the signature of Platoon Commander Milorad Pelemiš, who presumably would be expected to sign off on such a document. [See Attachment 1]

The controversy, if there is one, obviously centers on Mladić’s signature. It is controversial because there is a strong prosecutorial interest in the judicial validation of this document, but it is circulated exclusively in photocopy form and no original has ever been shown to anyone or even requested. Nor has any chain of custody evidence been presented. The last point (without minimizing the first) is important because of the specific history that surrounds this document. Presumably Erdemović brought it to Serbia with him in early 1996 when he arrived from Bosnia for medical treatment after the shootout with execution squad companions in Bijeljina. On 3 March in the evening, after the interview he gave to the French journalist Arnaud Girard, Yugoslav State Security arrested him and seized his personal papers and belongings. They kept this personal property at the time of his extradition to ICTY on 30 March 1996. The items were sent to the Tribunal only on 12 November 1996, shortly before Erdemović’s trial was due to begin at the Hague. No protocol of personal items forwarded by the Yugoslav authorities to the Tribunal has ever been shown; one simply assumes, without any particular evidence, that this is the way the Enlistment Contract came into the possession of the Prosecution. It popped up at the Milošević trial and it is sure to make an appearance again at the trial of General Ratko Mladić. But clearly the chain of custody for the Shroud of Turin is far more satisfactory than is the case with this key piece of Prosecution evidence linking with compelling directness Supreme Commander Mladić to a lowly sergeant in some obscure detachment so that all of Erdemović’s confessed evil deeds can be neatly imputed to Mladić without bothering to go through the chain of command, even for form’s sake.

To return to the first point as well, the widespread (not to say exclusive) use of photocopies as evidence at the Tribunal should be noted. Defence teams routinely fail to react, as they no doubt would in ordinary criminal cases before domestic courts, to demand vigorously that best possible evidence be made available for proper forensic analysis. At ICTY there is a tacit understanding by all parties, Prosecution, Defence, and Chamber, that asking for originals, whether they be documents or radio intercepts, is simply not to be done. This unspoken convention’s chilling effect on the proper verification of key evidence hardly requires elaboration.

We have, therefore, decided to perform a reductio ad absurdum on the Hague Tribunal. Instead of contesting the validity of Erdemović’s enlistment papers with Ratko Mladić’s signature, which would be futile, we decided to resort to Photoshop in exactly the same way that we suspect the Prosecution did. It was no technical challenge whatsoever to substitute in the document the signature of General Charles de Gaulle for that of General Ratko Mladić. [See Attachment 2] If photocopies are the best available evidence in the case, both versions of Erdemović’s Contract must be deemed equally authentic. How General de Gaulle, who passed away in 1970, could have signed an Enlistment Contract dated 1 February 1995 is a puzzle we leave to the Chambers of the Hague Tribunal to sort out.

The confused chain of command, however, is just one of the problems in this segment of Erdemović’s evidence. In the material sense, the figure of 500 additional prisoners allegedly slain back in Pilica later that afternoon is more important. Added to the alleged total in Branjevo, that makes about 1,700 Srebrenica victims, now a considerable way, about 20%, of the aggregate total of 8,000. So it is a matter of some significance to establish the authenticity of that figure of 500 prisoners allegedly killed in the Cultural Centre in Pilica in the final act of the execution drama Erdemović described.

It turns out that we have a case of double hearsay. Erdemović reported what Brano Gojković said to him about the number of those prisoners, and Brano Gojković heard it from the unidentified high ranking officer. After refusing to carry out these additional murders, Erdemović and several of his now tired fellow executioners went to a café across the street from the Cultural Centre, from where they could hear the shooting. But again, there is no percipient evidence about the act itself or the number of victims.

Whatever one may say about multiple hear-say in the testimony of “crown witness” Dražen Erdemović and about the number of individuals who according to him were executed at the Pilica Cultural Centre, in the Karadžić case the Trial Chamber decided to reinforce the impact of Erdemović’s evidence. But it was done in a manner so comical as to diminish the court’s public image even further, to the level of opéra bouffe.

Appearing before the Trial Chamber in the Popović case, Prosecution witness Jevto Bogdanović independently confirmed Erdemović’s story of the alleged execution of 500 prisoners at Pilica, but the manner in which that was done was quite remarkable. (It was noted that the day after the executions Bogdanović took part, along with other soldiers, in the cleanup operation in the Cultural Centre (Dom) at Pilica. See, Popović et al,, Transcript, May 10, 2007, p. 11329.) Footnote 18643 in the Karadžić trial verdict directs us to p. 11333 of the transcript in the Popović case, where Bogdanović gave evidence, and here is the relevant part of his testimony if we go where directed by the Karadžić Chamber:

Q. When you were drinking that day, could you say what it was you were drinking?

A. Rakija brandy.

Q. Where did you get that?

A. Neighbours, the locals, brought that to us. We drank for courage, to be able to sustain looking at the blood and the bodies, and the brains of the people.

Q. During the course of that day, did you hear anybody mention a number of how many bodies were in the dom?

A. I heard somebody on the road saying that there were 550, but we ourselves did not count.

So how is hear-say transformed at ICTY into an adjudicated fact? Based on double hearsay, which at the Hague Tribunal is a perfectly acceptable evidentiary tool, including an assertion relating to a key fact made by a witness who was admittedly drunk at the critical moment and who merely repeated in court what he heard, while in such condition, in passing and from an unidentified person. In a succession of judgments the resulting number of execution victims became enshrined as 500. [27] No reliable witness ever testified under oath before a court of law to having seen 500 prisoners at the Pilica Cultural Centre before execution, nor has any such witness confirmed under oath having counted their corpses subsequently. This account, verging on fiction, is totally unsupported by objective evidence but it is now part of the Hague Tribunal’s jurisprudence in four separate judgments. Is there another court in the world where such a thing would be possible?

V.

So much for the alleged witness-perpetrator Dražen Erdemović and his evidence. There are also two alleged survivors with equally interesting narratives, Protected Witness Q[28] and Ahmo Hasić, who testified variously under his own name and under pseudonyms. In order not to violate ICTY rules we will focus here only on the evidence he gave under his real name.

Witness Q. This witness’ evidence has to do with several different segments of Srebrenica events and we will discuss only the portion which refers to Pilica—Branjevo. In essence, Q has claimed that on 14 July he was bused with a number of other prisoners from the town of Bratunac, near Srebrenica, to the schoolhouse in Pilica, about 60 km to the north. There he spent two nights under unpleasant conditions. On 16 July busloads of prisoners were driven from Pilica to the farm field in Branjevo, about a ten minute ride, to be executed. Here is where some of the first significant anomalies in his evidence occur. In different trials Q testified variously that he and his group arrived at the execution site at 7 45 that morning,[29] between 9 00 and 9 30,[30] and “after 4 p.m.,”[31] with the executions in this version lasting into the night. The third time frame seriously conflicts with Erdemović’s account according to which it was all over by 3 to 4 p.m., depending on the trial he testified in. The commencement of the executions in the morning of 16 July also diverges considerably from what Erdemović said. The discrepancy is not just with respect to time, but also that according to Erdemović when he and his group arrived the field was empty, while Q claims that there already were a number of corpses there. But the spectacularly problematic aspects of Q’s narrative are yet to come.

The most intriguing question, of course, is how Q managed to survive and tell his story. Briefly, it happened as follows. When he and his group were lined up in the field, Q claims that without the usual preparations or order to “aim” and “fire”, the executioners simply began shooting. Miraculously, Q was faster and he fell to the ground face down and with his hands tied, dodging the bullet before it could strike him.[32]

Q’s hands were still tied behind his back as he lay on the ground pretending to be dead. He heard Serbian soldiers approaching the recently executed lot and heard one of them comment to the other, as they were getting nearer to him, that headshots are quite messy and to better stop administering the coup de grâce to head and shoot in the back because brains tend to splatter all over the executioner’s clothing.[33] But this gratuitous addendum to the narrative makes no sense. According to the laws of kinetics, in a situation such as Q is describing brains would splatter not from the entry hole upwards toward the shooter, but through the exit hole and downwards toward the ground. There was in fact no danger of the executioners soiling clothes with their victims’ brains. This has all the marks of a made up horror story.

In the next segment of the narrative, lucky Q cheats the bullet for the second time in the short space of a few minutes. As they stand above him, the coup de grâce administrators, so meticulous not to soil their clothing, follow the agreed plan to avoid shooting in the head. But being the bad shots that they are they miss Q’s back and instead the bullet passes just under his armpit, between the arms and the trunk of the body, without grazing him.

This is truly amazing when it is considered that Q’s arms were tied behind his back, which means that they must have been pressing tightly against the side of the body, leaving no gap for the errant bullet to pass through without damaging body tissue before harmlessly hitting the ground. This analysis would seem to be strongly supported by an examination of the image of the model in Attachment 3 who was tied up and positioned face down just as Q claimed he was. But Q’s astonishing scenario was accepted as authentic and his narrative was incorporated in all the Srebrenica judgments so far, with the exception of the Tolimir case. Even though Q gave evidence in that case as well, the Tolimir Chamber does not mention him in its judgment at all. If this is because they found his story too absurd, they certainly did not want to break ranks by publicly saying so.

That is the gist of Q’s account of the massacre of Pilica, which is supposed to corroborate executioner Erdemović’s narrative. Q then waits for nigh to fall and then he sneaks away from the killing field, as it is usually done in the movies under similar circumstances.

Ahmo Hasić. There are two main points of interest in Hasić’s evidence. The first, and most glaring, is of a statistical nature. It may be recalled that Erdemović referred to 1,200 execution victims in Branjevo and potentially another 500 at the Cultural Centre in Pilica. While giving evidence in the Popović case it seems that Hasić was inadequately rehearsed because he let a puzzling cat out of the bag. He said that as he was being driven by the Serbs in a bus toward the detention facility in Pilica he disobeyed instructions to keep his head down, sneaked a peek, and noticed that his group were being taken to the execution site in a convoy of seven buses.[34] That would hardly be enough vehicles to accommodate between 1,200 and 1,700 execution victims who are being taken on their final journey. Asked to estimate the capacity of each bus, Hasić put it at “50 or so”.[35] That would suggest a maximum capacity of 350 to 400 persons, considerably short of the number asserted in the narrative Hasić is enlisted by the Prosecution to corroborate.

At the time of the execution, like Q, Hasić says that the burst of fire preceded any command and it is not entirely clear how he managed to fall faster than the bullet flies, but he is alive, fortunately.[36] Then an extraordinary thing happened, at least the way Hasić tells it. Instead of administering the coup de grâce indiscriminately to all, Serbian soldiers decided to do it the easy way and “[w]hen the bursts of fire died down, one of them asked, ‘Are there any survivors?’ ‘I survived, kill me,’” Hasić quotes one victim as saying. “So they … would go from one survivor to another and fired a single bullet to the head.” This time they apparently were not concerned with the appearance of their clothing. At that point Hasić says that even he toyed with the idea: “I thought about notifying them that I was alive.”[37] Lucky for him, and for the Tribunal, that he resisted the temptation.

There seems to be no need to attempt any in depth critique of Ahmo Hasić’s report from the execution site. It speaks for itself and it is quoted merely to show what passes for evidence at the Hague Tribunal.

VI.

Finally, to complete the picture a brief review of the forensic data and how they were treated by the Tribunal is in order.

The forensic record with respect to the farm field in Branjevo is rather straightforward. In 1996 and 1997 exhumations were conducted by an international team of experts on behalf of the Office of the Prosecutor of ICTY.

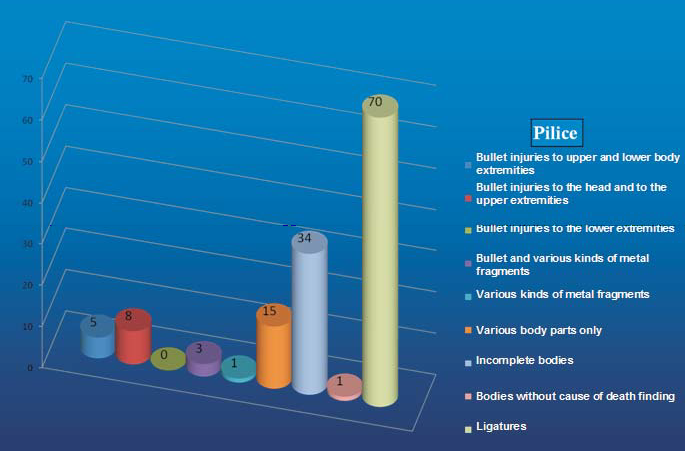

Breakdown of the content of the Pilica-Branjevo mass grave[38]

Pilica—Branjevo farm is notable for the number of bodies with blindfolds and/or ligatures. They number 70, or 51 % of the total number of cases examined here. That at least confirms that prisoners must have been involved in the executions. The remainder are mainly body fragments or incomplete bodies. With regard to the incomplete bodies from this mass grave, it may be noted from the graph that alongside some of them, in addition to a bullet, various metal fragments were found as well, while another portion had only bullet-related injuries, and the rest did not exhibit any injuries at all so that no cause of death could be determined. Of the 15 cases where only a small body fragment or a few bones were involved, cause of death could not be determined in 12.

There was a total of 137 “cases” in this mass grave, which following the classification methodology of Prosecution forensic experts is not the equivalent of 137 bodies. As shown in the breakdown, based on an analysis of the forensic team’s autopsy reports from this locale, 49 “cases” fall outside the category of complete bodies and consist of fragments or body parts. Giving a precise answer as to how many persons are buried in this mass grave is not an easy task. But if we take a conservative approach and deduct the 15 in the “various body parts category” from the 137 “cases”, we obtain a rough approximation of 122 bodies. If we go by pairs of femur bones there would be 115.

To this number we should perhaps add another 32 from other mass graves that were found to be DNA linked to Pilica—Branjevo. [39] The procedure of counting separately disarticulated body parts found in another grave may be questionable because it could be argued that it is still the same person, most of whose remains are at the original burial site. But since this methodology has been accepted in ICTY practice and the addition scarcely makes any material difference, we can avoid unnecessary contention by going along with it.

Adding up 122 bodies found in the Branjevo mass grave and 32 bodies presumably also originating from Branjevo, we have material evidence pointing to 154 murders at that location.

Interestingly, during Radovan Karadžić’s cross examination of Erdemović information turned up indicating that an earlier mass grave, possibly going back to World War II, may have in part overlapped with the Branjevo execution site.[40] That suggestion is corroborated to a limited extent by the fact that 14 autopsy reports[41] from the 1996 exhumation show remains that are completely skeletonised. Since disintegration of soft tissue generally takes four to five years, it is extremely unlikely that victims of a murder that took place a year and a half before exhumation would have skeletonised so quickly.

The forensic picture in Pilica—Branjevo is rather complex. It requires an analytical approach taking into account a variety of factors. But beyond strongly suggesting that a crime did take place there, and given the great number of ligatures that it probably involved prisoners, it does not lend much specific support to the narratives put forward by Dražen Erdemović and the two purported execution survivors.

VII.

We set out not to polemicise with the way the Hague Tribunal deals with evidence but to illustrate it and, in a particular case, to test its efficacy in empirically measurable terms. In a judicial setting “efficacy” has to do with whether a procedure assists or hinders the fact-finding process and therefore furthers or impedes the administration of justice. The test case we selected was the massacre in Pilica—Branjevo because it is probably the best documented of the several episodes, immediately after the fall of Srebrenica, in which Muslim prisoners of war were illegally executed by elements said to be associated with Serbian forces.[42] “Empirically measurable terms” refers to the availability of physical evidence (in this specific case, exhumed human remains and autopsy reports describing their condition) as opposed to the statements and impressions of witnesses. The latter are also potentially valuable fact-finding tools, provided they emanate from witnesses who are credible. Witness evidence, however, is known to be fraught with the subjectivities inherent to human nature. Its reliability is strengthened by the degree to which it conforms to the material evidence. That is why we have presented also a synopsis of the empirical findings resulting from exhumations conducted in the field. That enables us to compare key points in the various witnesses’ assertions to a backdrop of objective facts in order to test their reliability.

Viewing the picture thus as a whole, it clearly cannot be said that the evidence indicating that a massacre took place in Pilica—Branjevo is entirely fabricated. It would be more accurate to say that it was manipulated primarily in order to affect perception of the massacre’s scale and – in conjunction with similar manipulations of other post-July 11 episodes around Srebrenica – its legal characterization.

The principal percipient informant about what went on in Branjevo on 16 July and its scale is Dražen Erdemović. Q and Hasić are brought by the Prosecution merely for the atmosphere, to convey from their limited personal perspective the horror of what happened. Erdemović evidently is not a witness of truth, although he may have been there and some of the details he recounts might be accurate. He has an agenda, to get off as cheaply as possible and in the process to be rewarded by the Tribunal with various perquisites for being a cooperating witness. He inflates his numbers and adjusts his account to fit prosecutorial needs and expectations. The two “supporting actor” witnesses, Q and Hasić, simply overdo their roles. If all three of them had stuck to what they actually saw and experienced, instead of adding outright lies or melodramatic flourishes of such poor quality that it makes even a basically accurate story fall apart, we might now be in a better position to sort out what actually happened in Branjevo.

We are thus facing the enormous disparity between witness evidence, regularly given precedence by ICTY Chambers, alleging 1,200 to 1,700 murders in Branjevo, and corpus delicti evidence in the field indicating about 154. That is an impressive 10:1 disproportion. Can Tribunal skeptics really be harshly reproached for their caution under these circumstances?

Needless to say, the performance of these corrupt witnesses would have had no appreciable impact if only the Prosecution had faithfully executed its obligation to weigh the integrity of its evidence carefully before presenting it in court. And even if the Persecution, due to overzealousness, failed to meet that obligation, the vaunted Chamber of experienced professionals should have been alert to detect the absurdities in the witness’ testimonies, to exercise its prerogative of asking probing questions, and ultimately to give them the low credibility rating that they deserve.

The duty to act with integrity when presenting evidence is clearly spelled out for the defence in the ICTY Code Of Professional Conduct for Counsel Appearing Before the International Tribunalimposed upon the defence. In Article 23, Candour Toward the Tribunal, it is said:

(B) Counsel shall not knowingly:

(i) make an incorrect statement of material fact or law to the Tribunal; or

(ii) offer evidence which counsel knows to be incorrect. [43]

The same seems to apply to the Prosecution. It so happens that the Code of Professional Conduct for Prosecutors of the International Criminal Court [Draft version] in Article [7] (5) contains an analogous provision. Prosecution counsel are enjoined to “[N]ever knowingly make a false or misleading statement of material fact to the Court or offer evidence which he or she knows to be incorrect…”[44]

So the Prosecution and the Chamber are the main points where the system of evidence breaks down at ICTY. Under the doctrine that the judges are discerning professionals who cannot be fooled by most kinds of trickery, the Prosecution’s duty to be candid and to vouch for the quality of its evidence is practically suspended. It enjoys virtual carte blanche to use the courtroom as a stage to bring as its witnesses a wide array of charlatans who are permitted to expound their incoherent horror stories or wild misrepresentations for the benefit of an audience evidently far wider than the Chamber. The resulting media pressure and shaping of public perceptions are then reflected in the judges’ reluctance to challenge the defective evidence either during the proceedings or later in their judgments. The Court’s misguided preference for flawed evidence, and arrogant disdain for facts established through the use of time tested judicial techniques for distinguishing truth from fiction, has been the hallmark of Tribunal’s jurisprudence. Never calling the Prosecution to account for presenting evidence that is on the verge of misrepresentation and often plainly beyond the pale of credibility results for ICTY in a bitter harvest of widely disputed factual findings and highly questionable legal conclusions.

Endnotes:

[1] Be it noted that the Srebrenica massacre has been ruled a genocide in the Krstić, Popović, and Tolimir cases before various chambers of ICTY.

[2] That may not have been true in the past, as in ancient Athens where “the speeches the Greek orators constructed and presented in the Athenian courts of the fifth and fourth centuries BC indicate that in classical Greek law, trials were what we might call ‘at large’, meaning that nothingwas irrelevant. In a case on a contract, a litigant might remind the jury of how bravely he had fought against the Persians in the great victory at Salamis. We would say that the war record of the plaintiff or the defendant in a contract action was not relevant and could not be introduced into evidence.” See Stephen Wexler, Six Basic Ideas About Legal Proof: Lectures and aphorisms, p. 13, http://faculty.law.ubc.ca/wexler/legal_proof.html Oddly, ICTY in its practice may be returning to some form of the “at large” approach in the admission of evidence.

[3] http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/probative. Note be taken that the main source of TheFreeDictionary’s legal dictionary is West’s Encyclopedia of American Law, Edition 2.

[4] Ibid.

[5] http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/probative+value

[6] http://definitions.uslegal.com/p/probative-force/

[7] http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/proof

[8] NIOD Report, Part I: The Yugoslavian problem and the role of the West 1991-1994; Chapter 10: Srebrenica under siege.

[9] Debriefing on Srebrenica (October 1995), Pars. 2.20, 2.30, 2.34, 2.35, 2.38, and 2.43.

[10] In the view of several ICTY Chambers, they were forcibly expelled.

[11] Renaud Girard, “Bosnie: la confession d’ un criminal de guerre,” Le Figaro (Paris), 8 March 1996.

[12] For an exhaustive analysis of Erdemović’s evidence, see Germinal Čivikov, Srebrenica: The Star Witness [Translated by John Laughland], Belgrade 2010.

[13] Erdemović, T. 150.

[14] Erdemović, T. 150-151

[15] The fiction at the Hague Tribunal is that it operates on a fusion of the Common Law and Continental legal traditions. It is hardly disputed, however, that in reality it is the adversarial approach of the Common Law system that predominates.

[16] Le Figaro, op. cit. « L’ancien soldat qui rapporte ces faits a négocié avec le tribunal de La Haye. Contre la promesse d’une immunité et la possibilité de s’installer en Occident avec sa famille, il était prêt à tout dire. »

[17] The latest reiteration of this scenario was at the Karadžić trial, T. 25374 – 25375.

[18] See evidence at the Popović et al. trial, T. 10983: „According to my estimate, between 1.000 and 1.200.“

[19] According to the finding of the ICTY Chamber in Blagojević and Jokić, Trial Verdict, Par. 763.

[20] Ibid., Par. 349-350.

[21] The Chamber accepts the demotion as a proven fact in its judgment of 29 November 1996, Pars. 79 and 92. Erdemović was initially sentenced to ten years in prison on a plea agreement, but after he successfully challenged the basis for the agreement it was reduced to five years. He served a total of three years and a half in prison.

[22] See document OTP file number 04230390, Order to deploy of the Command of the Tenth Sabotage Detachment, 10 July 1995.

[23] Blagojević and Jokić, T. 10526.

[24] Popović et al., T. 14041.

[25] The Tolimir Chamber held unambiguously that soldier Brano Gojković was in command, Par. 493.

[26] OTP file number 00399985-6.

[27] See trial judgments in Blagojević and Jokić, Par. 355; Popović et al., footnote 1927; Perišić, Par. 715; Tolimir, Par. 500.

[28] He testified under different pseudonyms in various trials, but we will use here his initial in theKrstić case.

[29] Witness statement to the State Commission for the Compilation of Facts about War Crimes, Tuzla, 20 July 1996, p. 3. OTP file number 00950186-00950191.

[30] Witness statement to ICTY Office of the Prosecutor, 23 May 1996, p. 4. OTP file number 00798704-00798712.

[31] Karadžić, T. 24158.

[32] Statement to the BiH War Crimes Commission, 20 July 1996, p. 4.

[33] Tolimir, T. 30419.

[34] Popović et al, T. 1190.

[35] Ibid., T. 1198.

[36] Ibid., T. 1202-1203.

[37] Ibid., T. 1203.

[38] S. Karganović [ed.]. Deconstruction of a Virtual Genocide: An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Srebrenica. Den Haag – Belgrade 2011. Chapter VI, Ljubiša Simić: “Presentation and interpretation of forensic data (Pattern of injury breakdown”, p. 101. Den Haag – Belgrade 2011.

[39] These are: Kamenica 4, 1 body; Kamenica 9, 26 bodies; Čančari Road 11, 3 bodies; and Čančari Road 12, 2 bodies, for a total of 32.

[40] Karadžić, T. 25387-8.

[41] The following are the official ICTY designations of Pilica Autopsy Reports (1996) which are completely skeletonised: PLC-59-BP; PLC-61-BP; PLC-82-BP; PLC-106-BP; PLC-119-BP; PLC-123-BP; PLC-125-BP; PLC-127-BP; PLC-129-BP; PLC-131-BP; PLC-132-BP; PLC-134-BP; PLC-136-BP; PLC-138-BP.

[42] Regular or rogue is an issue we can set aside for the moment.

[43] http://www.icty.org/x/file/Legal%20Library/Defence/defence_code_of_conduct_july2009_en.pdf

[44] http://www.amicc.org/docs/prosecutor.pdf

Attachments:

[1] Erdemovic Enlistment Contract Signed by General Mladic

[2] Erdemovic Enlistment Contract signed by General de Gaulle