A series of articles published in 2009 about the “Bosnian War Crime Atlas,” a major and groundbreaking publication of the Sarajevo based Research and Documentation Center. While some of the Atlas’ many praiseworthy methodological breakthroughs and bold conclusions challenging many standard premises about the war in Bosnia merit respect, it is also beset by a number of flaws, particularly with regard to its treatment of Srebrenica related issues. We do not believe that those flaws are the result of mere oversight or incompetence, but attribute them rather to unacademic adherence to the “party line” on this particular issue of fundamental importance.

Mirsad Tokača’s Bosnian Crime Atlas

On November 4, 2009, Mirsad Tokača, director of the Sarajevo Research and Documentation Center (RDC), since defunct, unveiled the results of several years’ work: “The Bosnian War Crime Atlas.” [1] With the assistance of the Norwegian and other governments, Mr. Tokača’s institution worked assiduously to set up a comprehensive data base about missing persons from all the ethnic communities involved in the 1992—1995 war in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Our NGO, Srebrenica Historical Project, supported Mr. Tokača’s effort and considered it on the whole quite invaluable for an objective determination of the facts about some essential segments of the Bosnian conflict.

One of RDC’s important contributions to getting closer to the truth of wartime events are its data concerning the war’s total casualties. RDC suggests that the true figure is just under 100,000 for all three ethnic communities. That is in marked contrast to the reckless propaganda exaggerations while the conflict was still in progress, when some factually unsupported “estimates” reached as many as 250,000 or more victims, with predominant emphasis on one of the contending ethnic communities. The RDC estimate of Bosnian war casualties is roughly compatible with that offered by Ewa Tabeau, senior researcher and project leader of the Demographic Unit, OTP, ICTY, at an international conference in Berlin in 2010.

Tokača’s Center not only debunks irresponsibly inflated casualty figures, and not only does it offer a breakdown of victims by ethnic affiliation which roughly corresponds to each community’s share in the total BH population; it does more than that. By using an approach which appears to be scientifically irreproachable, it raises serious issues about a number of “sacred cows” left over from the Bosnian war of the 1990s.

In addition, Tokača claims as one of his project’s major achievements the creation of a “comprehensive and reliable data base” about each person killed in the war, by name and by place and manner of death, which “will be accessible to every citizen.”[2]

As part of his effort to ensure an impartial approach to these complex and often very sensitive issues, Tokača has demonstrated that he did have the courage to take on even the principal public protagonist in Bosnia of a methodology which is diametrically opposed to his, Amor Mašović, Director of the BH Missing Persons Institute. About Mašović and the work of his organization, Tokača had the following to say:

“There is nothing as easy as manipulating with victims. I expected much more from the BH Missing Persons Institute, but it is obvious that politics is dominant there, not professionalism. The search for missing persons must be detached from political influence and no politician, whoever he might be, has the right to come and tell them what to do. But there is plenty of that at the Institute, and in the various commissions before that, and that affects the victims’ families,” Tokača said. He pointed out that the Institute is in need of reorganization and that experts, not persons involved in politics, should be in charge of it.

“The present leadership of the BH Missing Persons Institute should be dismissed because that institution is filled with people who are deeply involved in politics. It is indicative that on the eve of every Srebrenica commemoration a new gravesite is found. Without disputing that there may be gravesites, the question remains why wait for July 11 for it to be opened or discovered?” Tokača said. [3]

It is difficult to formulate any effective objection to these thoughts. But when seen from a chess player’s perspective, Tokača’s moves — though truly admirable if viewed in isolation — could also be interpreted from another quite interesting angle.

Merely by glancing at the chessboard, the experienced Grand Master identifies his weakest pawns, which he knows that he will lose anyway in the course of the game. His strategy is not to save them at any cost but — on the contrary — to sacrifice them without hesitation in order to save the piece that he truly values.

An experienced and sophisticated man such as Tokača (in contrast to a local politico of Mašović’s caliber) must have grasped quite a while ago that in the long term most of the crude wartime propaganda fables were unsustainable. Whoever acts opportunely to discard those fabrications thereby gains enormous credibility which he can then invest in his highest value asset in the political contest. That is one of the fundamental principles of successful disinformation.

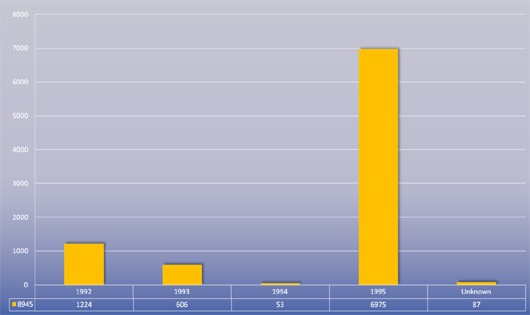

The attached graph, taken from the website of Tokača’s Center[4], suggests the answer to the question of what that high value political asset might be. The graph reflects with impeccable fidelity the trend in the number of victims for all the years of the war. Between 1992 and 1995 the declining trend downward is clear and unidirectional. That is entirely consistent with the known facts: the fiercest clashes occurred at the beginning, in 1992, and that explains why that is the year when the war claimed the greatest number of victims on all sides. After that, when the fronts stabilized, each year there were fewer victims. The accurate Tokača depicts that faithfully in his graph, but there is just one exception which spills the beans and therefore provokes critical questions. That is July of 1995, in other words: Srebrenica. For that month, the graph shows an upward spike which should represent about 8,000 victims, a phenomenon which is quite extraordinary in light of indisputable trends for the war when viewed as a whole.

Research and Documentation Center: Killed and Missing in Srebrenica (1992-95)

Were Tokača known for covering up his professional deficiencies and gaps in his arguments with intemperate rhetoric, as is the case with Mašović and others of the same ilk, this discrepancy between declared principles and specific results would not even attract attention. But it does, precisely because it stands out.

Since he has taken upon himself the obligation of placing before the public a comprehensive atlas of crimes where each victim will have a special place, not as a cipher but as a person endowed with a name, in a case of such capital significance as Srebrenica Tokača cannot now evade living up honestly to his own principle.

Does RDC, headed by Mirsad Tokača have personalized data, and that means the first and last name and other relevant details, for each Muslim victim of Srebrenica in July of 1995? Only two answers to this question are possible: Yes or No. There is no use pretending. If the answer is „Yes,“ then public presentations of the Atlas will be an ideal opportunity for Tokača to present to the world his sensational list of 8,000 Srebrenica victims.

If the answer is „No“ (or polite silence, which is the same) then we would advise Tokača to refrain in the future from criticising Mašović and his more than dubious and politically contaminated methodology. Otherwise, it really would be as they say in English: The kettle calling the pot black.

Endnotes:

[1] Politika (Belgrade), 8 October 2009.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Glas Srpske (Banja Luka), 12 October 2009.

[4] The graph is on the site of the Research and Documentation Center, http://www.idc.org.ba/presentation/research_results.htm . See: Srebrenica – municipality of suffering, graph no. 3.

A Bosnian crime, or disinformation, Atlas?

We made some comments about the “Bosnian war crimes atlas” created by the Research and Documentation Center [RDC] in Sarajevo, headed by Mirsad Tokača. Those comments were published before Mr. Tokača presented his findings to the public in their final form. For that reason, as is appropriate when commenting about something that we had not had an opportunity to examine fully, our reaction was rather restrained. But in the meantime, on November 4, 2009, Mr. Tokača did make his Atlas available to the general public,[1] and we are now at liberty to share our impressions with far less ambialence than was the case then.

First of all, an important qualification is in order. Tokača’s Atlas covers all of Bosnia and Herzegovina. We have neither the resources to verify his results on such a broad scale, nor is that within the scope of our research activity. We are dealing with the Srebrenica region only, and we can responsibly join a debate only in relation to events which took place there during the war in BH, between 1992 and 1995.

The electronic version of Mirsad Tokača’s Atlas is divided into three segments: (1) destruction of religious facilities; (2) locations, which refers to the areas in which the crimes were committed; and (3) incidents, which means specific examples of the crimes which were perpetrated, including a brief description and a list of victims.

We shall now proceed to critically examine each of these three segments of the Atlas, while making it clear that our focus will primarily be on possible errors in relation to the Srebrenica region, and only incidentally BH as a whole.

[1] Religious facilities. Facilities in this category are presented in the Atlas on a separate internet page.[2] If we may be allowed to step outside the self-imposed geographical framework (Srebrenica) and to cast a glance at BH as a whole, we shall notice here a very odd sight. The computer screen will literally turn green with little squares with the star and half moon on them, while behind them, skillfully concealed, lie twenty-six red squares with a cross (symbols of damaged Orthodox religious facilities) and several dozen blue ones, marking Catholic religious facilities which had suffered the same fate. If now, with the aid of the cursor, we were to go over to the portion of the map where the region of Srebrenica is located, it turns out that green squares are practically the only ones there. Only two are of the other colors. The latter are actually quite difficult to notice and even harder to click on because on Mr. Tokača’s map the green squares cover them over and make them practically imperceptible. The resulting impression is unambiguous and it is powerful: in Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole during the war it was almost exclusively Muslim religious facilities which suffered damage, while in the politically extraordinarily sensitive Srebrenica region, with minor exceptions, exclusively so.[3]

Does this picture bear any relation to reality, and if so, to what extent?

It would appear not to. Before us is a monograph by the late Professor Slobodan Mileusnić, “Spiritual genocide, 1991—1995” (1997).[4] On p. 9 of this richly documented study, which certainly ought to be on Mirsad Tokača’s bookshelf, we find the following information: “Serbian holy places and other historical monuments located on territories under the control of Croatian and Muslim forces are inaccessible and their fate is unknown, so that the list of 212 destroyed and 367 damaged churches is still incomplete.” Prof. Mileusnić carefully includes pictures of damaged and destroyed Orthodox religious facilities in Bosnia and Herzegovina that he is writing about, accompanied by a brief description of the damage, which is very similar to the approach used by Tokača in his Atlas. If, as we saw in footnote 3, broken windows qualify the mosque in Banovići Selo to be mentioned in this Atlas, what justification does Mr. Tokača have to mention just slightly more than two dozen of the 579 damaged and destroyed Orthodox religious places in Bosnia and Herzegovina which Prof. Mileusnić has duly recorded? This item alone is sufficient to raise serious doubts that in Mr. Tokača’s Atlas, at least in this section of it, something is drastically amiss.

Let us now focus on the region of Srebrenica, where the picture that Tokača presents raises many more doubts and questions, not only in regard to this but — as will soon be evident — the remaining two categories as well.

For Srebrenica town, only one Orthodox religious place is mentioned, and that is the town cathedral concerning which it is said laconically that “it was partially damaged, and then renovated after the war.”[5] Of Catholic holy places, only the „Bosna Srebrena“ chapel is mentioned, of which it is said that „it was partially damaged during the war, renovated in 2002.“

Is that really all that could be said about the damage that was done to Orthodox holy places in the region of Srebrenica during the conflict between 1992 and 1995? Not if we consult the research of Prof. Mileusnić. First of all, he notes not one but four destroyed and burned Orthodox religious structures in the town of Srebrenica, which is three more than Mr. Tokača was able to find. Then, he lists 17 for Srebrenica region: Drinjača, Kravice, Potpeć, Sase, Fakovići, Visočnik, Pribojevac, Žlijebac, Krnići, Erići, and Karna.[6]

It seems that mathematics is none too kind to Mirsad Tokača’s credibility: in the region, it turns out, there are 17 unmentioned churches, plus the 4 in the urban area of Srebrenica, making for a total of 21. Twenty-one, if we are not mistaken, is 21 times more than 1, which is the maximum that Mr. Tokača is prepared to concede to the Orthodox community as the extent of the damage that its religious facilities had suffered in the region of Srebrenica.

Prof. Mileusnić’s list should, however, be expanded to include the Orthodox church in Skelani which, during an attack by Muslim forces, fared far worse than the Banovići Selo mosque, with its broken windows, but nevertheless that was enough for the mosque to be included in Mr. Tokača’s annals.

But now, to all these missed opportunities to state the facts we must also add a puzzle. Readers will have to believe us (if they do not, they may go on location and check it out for themselves) that there is a destroyed mosque that the pedantic Mr. Tokača oddly neglected to mention. The location of that mosque’s ruins may give us a clue for this unusual failure. That mosque is located in Sase, a community about 12 km. from Srebrenica. Literally 20 meters from the mosque, which was destroyed by Serbs, there is the Serbian Orthodox monastery of the Holy Trinity. Muslim forces heavily damaged the monastery, and torched the monks’ quarters, during combat which took place in the area in 1992-1993. [7]

The ignored mosque in Sase fared incomparably worse that the one in Banovići Selo, with its broken windows: it was razed to the ground. Did that not merit being noted in a scholarly presentation of this caliber?

We assume that, in relation to the politically crucial Srebrenica region, any suggestion of symmetry would be anathema to Mr. Tokača and his “independent…professional, non-government, and unbiased institution.”[8] Something tells us that might have been the reason Mr. Tokača managed to get over the destroyed mosque: just so that he would not be obligated to mention the heavily damaged monastery located just a few steps away.

But this story is not just about the suffering of two religious places and about the hypocritical, politically motivated, coverup of that double crime. There is more to it than that. In happier and more normal times, these two temples which stood side by side and where neighbors prayed in different ways to the same God, were linked in a wondrous way. It so happens that local Muslims made donations to the monastery for the building of its living quarters, while members of the Orthodox community contributed to the building of the mosque. That is why the politically inspired avoidance of the fate of these two temples in Mr. Tokača’s Atlas is not just a mistake, but something much more serious than that—it is a huge shame.

(2) Locations

In relation to the very significant issue of Srebrenica victims, in the segment which depicts Locations, the RDC Atlas offers the following information:

| Murdered Serbs | 421 |

| Missing Serbs | 8 |

| Murdered Croats | 5 |

| Missing Croats | 1 |

| Murdered Bosniaks (Muslims) | 4,256 |

| Missing Bosniaks (Muslims) | 2,673 |

| Total: | 7,364 |

To be quite clear: when we click on Srebrenica on the RDC Locations site, there appears a window with a long list of victims by name. There is no ethnic breakdown as such, or we were unable to find it. But regardless, names are most often sufficient to make the distinction and we counted the Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks (Muslims) on that list and came up with the results shown above. It is not said explicitly, but in the way the data are presented it is implied that the total figure of 7,364 represents the number of victims during the entire period of the war, from 1992 to 1995.

Once everything is broken down by category, the first thing that strikes the eye is the determination of the authors of this Atlas to make sure that the final figure for the politically crucial region of Srebrenica approximate as closely as possible the magic number of 8000 victims. To that end, and to bolster the total, even Serbian war victims are enlisted, over 400 of them who are acknowledged as such by the Atlas, as well as the considerable figure of Muslims of whom it is said that they are “missing,” over 2,600 of them. (Nobody has so far bothered to explain how someone can be charged with “genocide” in relation to disappeared persons, but that is another topic.) As the case may be, the category of “Murdered Bosniaks (Muslims)” numbers about 4200, according to the records of RDC and Mr. Tokača. That is but half way to the magic number, and even that figure—assuming it is reliable—to be useful needs to be broken down into prisoners of war who were actually executed in July of 1995, those who were killed in combat during 28th Division’s breakthrough toward Tuzla after Serbian forces captured Srebrenica on July 11, as well as persons who were killed in various other ways and times, including those who died of natural causes, in the period from the beginning of the conflict to July 11, 1995.

So it turns out that, if we pose but a handful of critical questions, we see that even the figure of 4,200 murdered Muslims is not what at first glance it appears to be, and that the general figure of “7364 victims” is not that as a matter of certainty. Quite the contrary, for a project with scholarly pretensions, that general figure is unforgivably misleading.

That should be ample cause to challenge the entire construct, insofar as it purports to deal with Srebrenica. However, dilemmas only increase if we compare the above data, made officially public on November 4, 2009, with information pertaining to the region of Srebrenica which is to be found in a separate entry on the RDC website, entitled “Srebrenica—a place of suffering.” [9] To make those statistics more readable, we present them here with the number of the graph where they may be found:

Srebrenica: murdered and disappeared, 92—95 (Graph 3)

1992: 1224

1993: 606

1994: 53

1995: 6,975

Unknown: 87

Total: 8,945

Srebrenica: murdered and disappeared, 92—95 (Graph 4)

77,98% Srebrenica victims date from 1995

Srebrenica: murdered and disappeared, 92—95 (Graph 8)

Victims in July 1995: 6,886 (N.B: shouldn’t the total be 6,929 if the two figures were properly added up?)

Srebrenica: murdered and disappeared by ethnicity (Graph 13)

Bosniaks (Muslims): 8,460

Serbs: 480

Srebrenica: murdered and disappeared by status and ethnicity (Graph 15)

Serbian civilians: 151

Serbian soldiers: 329

Clearly, these figures are uncoordinated with the other Atlas data. Let us note just Graph 3, entitled “Murdered and disappeared, 92—95.” RDC has been circulating this, and other graphs in the same presentation, for over a year. In that (perhaps interim) version of his Srebrenica data, Mr. Tokača shows that, according to the information at his disposal a year or more ago, there were about 9,000, or, to be precise, 8,945 victims. According to the calculations presented in the Atlas, that figure as it stands today has dropped to 7,350. Thus, about 1600 victims have simply vanished in some inexplicable way. This apparent “fixing” of the data had as its consequences that the total of victims—according to Tokača’s position now—has fallen below the magic figure of 8,000, although not by much. Are there serious scholarly reasons for this correction in the data? Or, was that done for practical reasons, to jettison utterly unsustainable claims in order to build up credibility for insisting on the preservation of the core of the official Srebrenica narrative? We do not have a reliable answer to that question.

In any event, it is interesting that according to the graphs which were circulated over a year ago it would appear that between 1992 and 1994 about 2,000 people had lost their lives in the region of Srebrenica. That opens up some fascinating issues: where and how are those individuals recorded, where were they buried after their deaths and what measures have been taken to ensure that they would not end up at the Potočari Memorial center, where they would be untruthfully presented as victims of genocide from July of 1995?

Deviations of a few dozen, or even hundreds, can be tolerated if they are within reason. But there is something else here that stares one in the face as we carefully and critically examine how these data are laid out. That is the consistent reliance on the fairly large category of “disappeared” to stuff the total of presumed victims and thus raise their number to the desired statistical level. That would still be true even if we assumed that everyone from the “murdered” category could be classed as a victim of the execution of war prisoners in July of 1995, whether we considered it a massacre or genocide.

It would be useful to clarify the concept of “disappeared” as it is generally used in these situations. It simply means the following. At a certain moment, most likely soon after the takeover of the Srebrenica enclave in July of 1995, a relative or some other person called to inform the International Red Cross, or some other analogous organizations, that as far as the declarant was aware, at the time of reporting, the individual in question was missing. There were several such, rather lengthy, lists of missing people in circulation at the time. Those lists were notorious for frequently duplicated data involving the same individual because of multiple sources, which is quite natural given the chaos and confusion at the time. But the point to bear in mind is that the job of the organization which received the missing person report was only to make a note of it, not to conduct an investigation to ascertain the status or the ultimate fate of the individual reported to be missing.

These lists were undoubtedly of great help initially, but they cannot serve as a source of reliable data about a person’s ultimate fate. Deleting duplicate reports was a sufficiently thankless, and never quite completed job, of the various commissions which were subsequently looking into these matters. Ascertaining the final status of the “missing person,” and whether that individual ever surfaced somewhere else after the end of the war, is a task that nobody ever even attempted to systematically perform.

That is the reason why, in this particular context, relying on the “disappeared,” or “missing,” as a meaningful category in terms of who was executed can only serve to obfuscate, not to clarify, the facts. It is, therefore, a category that we should regard with the most extreme skepticism.

When we put aside the “disappeared,” and when from the figure of 4,256 “murdered” Bosniaks we deduct at least the 2,000 that the ICTY Prosecution military expert Richard Butler said could be the number of those killed in combat during the retreat of the 28th Division column from Srebrenica to Tuzla, we obtain a figure of 2,500 which is much more realistic, and closer to the forensic evidence from the mass graves. The results of mass grave exhumations, let us recall, are the only corpus delicti of the Srebrenica crime and they must therefore serve as the point of departure for any factually based discussion on this subject.

Like all bold bluffs, this one also stands a chance of succeeding under one condition only—that no one should bother to check it out. We saw that clearly in the case of the forensic evidence put forward by the Hague Tribunal Office of the Prosecutor. It consists of over 30,000 pages of material which seemingly document about 3,500 Muslim Srebrenica victims. The Prosecution no doubt hoped that nobody would read or critically examine that material, and that by inertia it would be accepted as reliable and just in the way the Prosecution chose to present and interpret it to the chamber and to the general public. Indeed, as expected, laziness was for a time triumphant and for a number of years the Tribunal’s bluff looked authentic and rather intimidating. But when a forensic specialist on the team of our NGO checked the entire material, from the first page to the last, the picture changed radically and the Hague Prosecution’s construct of forensic “evidence” collapsed unceremoniously, like a house of cards.[10]

The same applies to the list of Srebrenica victims in Mr. Tokača’s Atlas. We were not discouraged by the scope of the material and we did not give up on verification. As in the other case, we analyzed everything thoroughly, from start to finish. The result is clear and unambiguous. At least as far as the Srebrenica victims’ list is concerned, we cannot give Mr. Tokača a passing grade.

(3) Incidents. In addition to the already enumerated doubts about the integrity of Mr. Tokača’s Atlas, there remains one more and it concerns the category that he calls “incidents.” The examples in the Atlas in this category are again very one-sided, and they are presented in a way that does not befit an “unbiased” organization.[11]

First of all, and in order to remove every possibility of terminological misunderstandings, what does the word “incident” mean? We consulted two respectable sources, the Oxford dictionary for the definition in the English language, and the Vujaklija dictionary for the Serbian-Croatian-Bosnian definition. Here is what the Oxford has to say:

incident

- noun 1 an event or occurrence. 2 a violent event, such as an attack. 3 the occurrence of dangerous or exciting events: the plane landed without incident.

- ORIGIN from Latin incidere ‘fall upon, happen to’.

According to Vujaklija (a Serbian etymological dictionary), first in the original:

инцидент (л. incidens), латиницом: incident

догађај, случај, непријатан случај; замерка, приговор, примедба, упадица; споредан догађај, споредна радња; мали сукоб.

And now the relevant part of the definition in English: “an event, occurrence, an unpleasant occurrence; …a secondary event or action; a small-scale conflict.”

Both linguistic authorities describe “incident” in general terms as, first of all, an event, then they define it more closely as an unpleasant event (Vujaklija) or an event accompanied by violence (Oxford).

Does Mr. Tokača’s Atlas list all unpleasant occurrences and events in the region of Srebrenica during the conflict from 1992 to 1995 that were accompanied by violence? No, it does not. Almost all such incidents where the victims were citizens of Serbian ethnicity are omitted. If that is correct, it is unacceptable.

The first and fundamental test of the objectivity of Mr. Tokača’s Atlas in this regard is the question: how many “incidents” does it mention where Serbian villages and hamlets surrounding Srebrenica were attacked and destroyed? The answer is: not a single one. If the attack on a Serbian village, the indiscriminate killing of its inhabitants irrespective of gender or age, the destruction of homes, schools, and other infrastructural facilities, and plunder of property, according to the definitions presented above, does not constitute an “incident,” then what does?

An exhaustive list of those villages and hamlets would be very lengthy. We will mention only some that we visited during the last couple of months where we have ascertained personally the thoroughness of their destruction: Ratkovići (wiped off the face of this earth), Zalazje, Obadi, Andrići, Krnići, Medje, Karno, Pribićevac, Bradići, Gaj, Toplica, Brežani, Arapovići, Božići, Klekovići, Brana Bačići, Kravice, Jezero, Mala Turija, Podravanje, Bjelovac, Bukova Glava, and Pribojevići. Our non-government organization has detailed files on the condition of those and many more villages, including pictures which reflect their appearance immediately after attack during the war, and their condition today, a decade and a half later. It will be our pleasure to place those records at the disposal of Mr. Tokača should he be prepared to fill the gaps in his catalogue of war incidents in the area of Srebrenica by including also those incidents in which the victims were Serbs.

To conclude. The shortcomings that we have cited seriously undermine the integrity of the Bosnian war crimes Atlas that was prepared by the Research and Documentation Center of Mr. Mirsad Tokača. We have pointed out the systematic ignoring of damage and victims, with a very strong suggestion that it was done based on ethnic affiliation, when the destruction of religious facilities occurred and inhabited areas and their human residents were victimized, if they happened to be Serbian. Mr. Tokača’s depiction of the human toll of the ethnic conflict in the region of Srebrenica between 1992 and 1995 is, to put it charitably, deceptive and inaccurate.

Mr. Tokača’s Atlas contains many useful insights and data, but in order to be a scholarly work in the authentic sense of that word it needs to exhibit one more feature: objectivity. The inclusion of some correct data (and Mr. Tokača does provide a considerable amount of it) is not in and of itself a criterion, but only one of the incidental conditions, of scholarship. Where that is done not out of regard for the truth, but as a tactic to promote an agenda in relation to a specific cause that the author happens to be committed to, the work as a whole may then have to forfeit its scholarly credentials.

If we were to offer a critical overview of the Bosnian war crimes Atlas, implicitly it is entirely under the shadow of Srebrenica and it is animated by the determined defense of that last bastion of wartime propaganda and key buttress of the Muslim side’s current policy toward the Republic of Srpska. Absolutely everything is subject to discussion and may even be the subject of revision except—Srebrenica. For Srebrenica, the principle of victims of the first and second order is still unconditionally in effect; or, to be more exact, of acknowledged and invisible victims. The acknowledged victims are Muslim, the invisible ones are Serbian.

The credo of the Research and Documentation Center, which is conspicuously emblazoned on its internet site, is: Truth today—peace forever. A noble thought. But if the results that we have just reviewed reflect the concept of truth which animates Mr. Tokača, the prospects for eternal peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina are slim indeed.

Endnotes:

[1]http://www.idc.org.ba/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=80&Itemid=83&lang=bs

[2]http://www.idc.org.ba/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=22%3

[3] Mr. Tokača’s criterion is very flexible and broad. He refers, for instance, to the mosque in Banovići Selo, municipality of Banovići, and he reports that „due to military operations, [its] facade and windows were damaged.“ Fair enough. No damage or desecration of any kind may be inflicted on religious temples. However, the same minimal level of tolerance for damage to religious sites should be applied equally to temples of all confessions.

[4] Published by the Museum of the Serbian Orthodox Church, Belgrade, 1997.

[5] It is correct that the Srebrenica town Orthodox temple had to be renovated after the war, but the reason is that while Srebrenica was an enclave under Muslim control the church was desecrated and turned into a storage deposit. Had Mr. Tokača’s assistants bothered to take a few hundred meters’ stroll down the main street to the Srebrenica Orthodox cemetery, there they would have noticed—next to desecrated headstones—also the heavily damaged cemetery chapel on whose façade and interior the effects of firearms are still clearly visible. With what justification was it omitted from the Atlas?

[6] Op. cit., Mileusnić, page. 153.

[7] Op. cit., Mileusnić, page. 169.

[8] See section, „Dobrodošli na web portal IDC [Welcome to the RDC web portal],“ http://www.idc.org.ba/

[9]http://www.idc.org.ba/index.php?option=com_content&view=section&id=35&Itemid=126&lang=bs

[10] See study by Dr. Ljubiša Simić, http://www.srebrenica-project.com/sr/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=19&Itemid=17

[11] For the way RDC describes itself, see footnote 8.

Deception or, as Mr. Tokača would call it, the “Bosnian War Crimes Atlas”

Given modern technology most things today are practically impossible to hide. There are still those with such vested interests that they are scarcely in a position to discuss wartime suffering in a frank and open manner, and even if they were so inclined their mentors would never allow them to do so in a professional and honest way. As a result, we still cannot take assertions made by Mr. Mirsad Tokača of the Sarajevo-based Research and Documentation Center at face value. We must always keep checking and rechecking whether Mr. Tokača is really prepared to apply the same standards to all victims of the recent war in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

If one were to start with a critical review of his treatment of religious facilities, one will notice on their site, http://www.idc.org.ba/, a significant discrepancy between the treatment of Orthodox churches and mosques. Almost as a rule, churches are hidden, masked, scarcely noticeable. That might be the fault of Mr. Tokača’s technical assistants, for all we know. But what definitely undermines his credibility is the number of destroyed Serbian temples that he is prepared to list. For the author of a widely touted reference work on wartime crimes, no more than 26 Orthodox churches were razed in all of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Just based on the data available in Prof. Slobodan Mileusnić’s documented study “Spiritual genocide,” it is clear that over 150 Serbian churches were destroyed and several hundred were damaged. That suggests that in Mr. Tokača’s Atlas something is seriously awry.

This approach is particularly patent in the politically crucial Drina River valley where the region of Srebrenica happens to be located. In order to preserve the last propaganda bastion of the Sarajevo political “elite”, Mr. Tokača is compelled to take his falsehoods and disinformation to the highest practicable level. Not only does he disingenuously report damage to just one Orthodox church and one Roman Catholic chapel in Srebrenica, but he goes a step further in deftly manipulating his presentation of data about victims. Today, given the omnipresence of technology, the number of those who would be reckless enough to do that would be very small indeed.

Where the Atlas refers to incidents involving the murder of innocents, or the devastation of their villages, if the victims were Serbs they are largely ignored. However, if they happen to be Muslim, Mr. Tokača is very meticulous in identifying each victim and describing each incident, even if it involves no more than one person. From our standpoint, there is nothing whatsoever wrong with that. But a cursory review of Mr. Tokača’s Atlas will reveal that he has left out dozens of devastated Serbian villages and that he nonchalantly ignores hundreds of Serbian victims. For him, the murder of old people and children, ranging in age from 15 to 90, and the total destruction of Serbian villages such as Ratkovići, Podravanje, Krnjići, Andrići, Zalazje, Brana Bačići, Obadi, Bukova Glava, Gaj, Karno, Medje, Brežani, Špat, Božići, etc. does not constitute an incident, in spite of the fact that in those villages some of the victims, who were approaching the ninth decade of their lives, were murdered, or burned to death, in their own homes.

Isn’t that a bit extreme, even for those who are generally prepared to do anything in order to maintain the Srebrenica myth, regardless of the price?

Yet, side by side with the invisible Serbian victims, in the category of incidents and crimes which are recognized as such by Mr. Tokača and his associates there are some victims who appear to have been killed twice in different locations and who therefore have earned the right to be inscribed in the Atlas twice as victims of the war. They are Muslims, of course. One of them, Omerović Selmo, born in Bratunac, according to Mr. Tokača was killed three times at three different locations.

To avoid any possibility of misunderstanding, we are referring to the locality of Glogova where, in his incidents category, Mr. Tokača presents data about Muslim victims who lost their lives in and around that village.

Before going further, we should remind Mr. Tokača and his staff that the victims of Glogova did not all belong to just one ethnic group. On November 6, 1992, Bosnian Muslim forces under the command of Naser Orić staged an attack on Serbian positions in the area of Glodjansko brdo. In that attack, they took 52 Bosnian Serb soldiers prisoner. From that point on, pursuant to the relevant provisions of the Geneva convention those soldiers acquired the status of protected persons, exactly the same as captured Bosnian Muslim soldiers in July of 1995. These Bosnian Serb prisoners of war were liquidated on the spot: they were shackled and tortured and then they were killed in the most brutal fashion, using dull objects and knives, with body part amputations. In February 1993 the remains of 42 of these massacred Bosnian Serb soldiers were found in 7 mass graves. Post mortem examinations were conducted by Dr. Zoran Stanković of the Military Medical Academy in Belgrade. The bodies of ten of the prisoners taken by Naser Orić’s forces have not been found to this day.

In the section of the Atlas which refers to Glogova there is no mention of these war crimes victims, whose status as such is unchallangeable even by Mr. Tokača’s standards. Why?

For each incident which, following the monoethnic principle, is mentioned in this section of the Atlas, Mr. Tokača lists the victims. According to these parameters, the total number of victims, with first and last names, for the locality of Glogova is 101 [see Annex 1 – 6] Of that number, the names of 35 persons are listed twice in relation to at least two locations, while one person is listed as having died in three different locations. That suggests that in Glogova there are persons who died two, or even three, times. Why is Mr. Tokača risking the discreditation of his work by such shabby practices? Who gains from such a distorted and one-sided misrepresentation of the identity of the victims, and of the Bosnian conflict as a whole?

How to explain the Atlas’ silence about the Serbian soldiers killed at Glogova in 1992, whose status as victims is not disputed even by the Hague tribunal? For Mr. Tokača, that incident never occurred. In his Atlas, it would seem that Serbian victims are unwelcome or are but grudgingly admitted, particularly if they happen to be from the general area of Srebrenica. That is the geographical point where the thesis which holds that Muslims were victims and Serbs perpetrators must be tenaciously upheld. Within the confines of that approach, it is natural that there is no room for Serbian victims. If their existence were to be admitted, responsibility for crimes would have to be shared by the Muslim side, an outcome that is certainly abhorrent to those who are committed to blaming only one side in the conflict, in this case the Serbs.

Figuring that nobody would take the trouble and spend the time to critically examine his material, Mr. Tokača has frivolously undermined his and his institution’s reputation. The seeming puzzle after all is not such a great mystery, being rather only the tip of the iceberg. The real threat to the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina are the discreet actors unseen by the public. They are, metaphorically speaking, the part of the iceberg which is submerged under water. From the safety of the murky waters which shelter them, they decide what is true and what is false, who is right and who is wrong, who are the victims and who are the perpetrators, what is just and what is unjust. It is they who are pulling the strings in Bosnia and Herzegovina, while Mr. Tokača and others like him only have the menial task of carrying out decisions they made and formulated beforehand, in this case in the form of the Bosnian Crime Atlas.

And by the way Mr. Tokača, have you heard of Kravica?

Every Orthodox Christmas is a good time to keep refreshing Mr. Mirsad Tokača’s memory of war crimes. On January 7, 1993, armed forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina from Srebrenica, under the command of brigadier Naser Orić, attacked and devastated the Serbian village of Kravica, about 10 km from Bratunac. The human cost of the attack (or shall we call it „incident,“ in deference to the terminology preferred by Mr. Tokača in his Bosnian Crime Atlas?) was at a minimum 34 persons, if we exclude rumors and confine ourselves just to the bodies which were subsequently located and on which a proper autopsy was conducted on March 18, 1993.

A careful perusal of Mr. Tokača’s Atlas does not disclose any reference to this particular crime which, later, became a point in controversy at the trial of Naser Orić before ICTY at the Hague. The attack on Kravica, however, with all its attendant mayhem and destruction, should have been hard to miss for a Defence ministry official like Mirsad Tokača who, only three months earlier, on September 4, 1992, was appointed by the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo to the post of secretary to the State commission for the collection of evidence of war crimes.[1] It is specified in par. 3 of the Minutes of the relevant Presidency meeting that the Institute under which Mr. Tokača’s Commission was to be operating would have no „political or propaganda“ goals and that the Commission would keep the Institute abreast of its findings by means of regular reports.

The natural reading of the Presidency’s instructions is that Mr Tokača’s wartime Commission, in much the same way as his present-day Research and Documentation Center, was given a mandate to deal neutrally with all war crimes, no matter by whom and against whom committed. Such an unbiased approach should have been only fitting for a government in good standing with the international community which, theoretically at least, the Sarajevo Presidency at that time was. It was the political thesis of that government, one of whose civil servants Mr. Tokača[2] was, that it was the only legitimate authority in Bosnia and Herzegovina, that it was democratic and multicultural, and that it represented, on a basis of equality, the interests of all constituent groups in the country.

Did Mr. Tokača’s Commission for the collection of evidence of war crimes do any investigations following the attack that the Presidency’s army conducted on the village of Kravica on January 7, 1993? If not, why not?

But let bygones be bygones. We can move forward, and we do not have to talk about Mr. Tokača’s involvement with Kravica, or lack of it, then. We can talk about it now.

In his new incarnation, as director of the Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo, an institution which has acquired a considerable reputation as an objective data collection center, Mr. Tokača has, we are afraid, much less room for creative maneuvering than he used to have during the war. He is no longer working for some “Presidency” with dubious credentials, he is now accountable to the general public and to the judicial institutions where he often gives evidence as an expert witness and which rely enormously on the accuracy of his data. His performance now does not affect only his own and his institution’s credibility. By failing to meet professional standards, he also risks severely disappointing his distinguished sponsors, the Foreign Ministry of the Kingdom of Norway and the Swedish International Development Agency, to mention just a few.

So it is a very important issue how in his Bosnian War Crimes Atlas[3] Mr. Tokača treats the attack on Kravica by Bosnian Muslim forces, which occurred on January 7, 1993, and the subsequent massacre of its inhabitants who did not manage to flee. That is a litmus test of his objectivity and neutrality in relation to the victims of the recent war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, regardless of their ethnicity. The display of such virtues may have been just too much to expect from a Defence ministry official turned war crimes investigator in the midst of a bitter ethnic conflict, but it is properly to be expected of him now. If that expectation exceeds his capacities, he should tender his resignation and let a better man take over.

A careful review of the relevant portion of the Bosnian war crimes atlas leads one to the disappointing conclusion that, as far as Mr. Tokača is concerned – or is willing to admit – nothing unusual whatsoever happened in Kravica on January 7, 1993. Strangely, Mr. Tokača is not similarly uninformed about events in the neighboring village of Glogova, which occurred in roughly the same time period, [4] when a number of Muslim inhabitants were massacred in the course of a Serbian attack. And just as surprisingly, he seems to be very well briefed on events in the general neighborhood which occurred in July of 1995. Two examples should suffice.

An icon on his Google map leads us to the village of Sandići, which is walking distance from Kravica on the Bratunac – Konjević Polje road. The entry is dated July 16, 1995, and it contains the following information: “Village of Sandići. Description: According to the allegations of a witness, ‘when the convoy with refugees from Srebrenica reached the village of Sandići, I saw on a pile the bodies of executed Muslim civilians. There were about 200 of them. Later, I heard that the corpses were incinerated.’”

The alleged incident may or may not have taken place, but by all accounts the supporting evidence for it is flimsy indeed. How did the witness, who was riding on a bus which presumably just drove by, know that the victims were civilians? What opportunity did she have to ascertain their number? What is the practical purpose of the hearsay report that the bodies were later burned,[5] except for its emotional shock value?[6]

The second item has to do with the Kravica Agricultural Cooperative, where on July 13, 1995, several hundred Muslim prisoners were killed by Serb guards. What Mr. Tokača offers in terms of back up evidence for this allegation are three indictments, two current ones against defendants facing trial before the Bosnia and Herzegovina War Crimes Tribunal in Sarajevo, and one against General Krstić, a decade ago. An indictment is not the same as a judgment, which usually is announced after a trial and after a review of the evidence. We do not dispute that this terrible crime happened and we agree that those who were involved in its commission should be punished. But basic honesty and respect for users of the Atlas requires that it be duly noted that this is not yet a judicially settled fact. The crime may be undisputed, but its dimensions, the culpability of the individual accused, and its place within the context of the Srebrenica massacre are all very much open and controversial issues.

Mr. Tokača’s portrayal of wartime events in and around Kravica, sloppy and essentially unprofessional as it is, at least demonstrates that when he was creating his Atlas, victims from this village and its environs were very much on his mind. That makes his omissions with regard to Serbian victims of the war in exactly the same area, specifically in Kravica and its surrounding hamlets, doubly scandalous.

Mr. Tokača may, of course, offer the justification that in the few cases which dealt with Kravica – one, to be exact, in the prosecution of Naser Orić – the court did not draw any legal conclusions about the number and identity of the victims. That is true, but the prosecution did not allege any, so the chamber had nothing in this area to rule on.[7] While that may have been a handicap for the chamber, it should not have been for Mr. Tokača, as evidenced by the rather liberal standards for the admission of evidence that he practices in cases involving Muslim victims, of which the two from Sandići should serve as sufficient examples. The dossier prepared by the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Srpska, containing the findings of the post-attack investigation that they conducted in the 1993 Kravica incident, including detailed forensic reports for 34 individuals, should constitutes evidence that would be admissible according to a much higher standard.

Unlike ICTY prosecution spokesperson, Florence Hartmann, who drew a sophistical distinction between military personnel and civilian victims in Kravica in order to downgrade the number of innocent victims resulting from the attack,[8] Mr. Tokača is not bound by that distinction because he puts it as his mission to record both categories of war related losses. But even if he were to choose Ms. Hartmann’s lower figure of 13 “innocent civilians” for the Christmas massacre in the village of Kravica which the ICTY Office of the Prosecutor accepts, why aren’t even those 13 Serbian victims listed in his Atlas?[9]

It is sad that what once appeared to be a promising project, with great potential to shed an objective new light on wartime events in Bosnia and Herzegovina, now seems to have degenerated into a typical Balkan hatchet job.

Endnotes:

[1] Minutes of the 161st Session of the Presidency of BiH, September 4, 1992, no. 02-011-669/92.

[2] Interestingly, the Presidency Minutes are prefaced with the statement that “Territorial defence, HVO, and other armed units are an integral part of the army.” Could there possibly have been a conflict of interest for a Defence ministry official, now secretary of the war crimes commission, investigating suspected crimes allegedly committed by his recent colleagues?

[3] See RDS internet portal: http://www.idc.org.ba/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=80&Itemid=83&lang=bs

[4] See our internet site: http://www.srebrenica-project.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=80:deception-or-as-mr-tokaa-would-call-it-the-bosnian-atlas&catid=12:2009-01-25-02-01-02

[5] If the woman had stated that she “heard” that extraterrestrials had come and taken away the bodies, one wonders if Mr. Tokača would have recorded it as part of his incident description.

[6] As long as we are talking about Sandići, the meticulous Mr. Tokača notes in a separate entry, „Sandići field,“ that according to prosecution allegations in the Kravice agricultural cooperative case, a captured male of Bosnian ethnicity was executed in that particular field. Never mind that the trial is in progress and that the matter has not been adjudicated, let us assume that it happened as alleged. What this shows is Mr. Tokača’s great care to record even a single Muslim victim allegedly executed in a field. That makes his silence about the dozens of murdered Serbian villagers in the concerted Christmas attack on Kravica all the more inexusable.

[7] In par. 25 of his indictment, Orić was charged with killing a total of 8 persons, all of them unrelated to Kravica.

[8] See ICTY Weekly press briefing, 6/7/2005.

[9] If prosecutorial allegations are sufficient to list the Agricultural Cooperative massacre of Muslims, the same principle should apply to the village massacre of Serbs.